The following is a reflection on the 2019 piece Count In by composer Daniel Corral. In this essay Corral lays out his creative process alongside formal elements of the piece, while considering experiences of stability, change, and presence. Click here to watch/listen.

Intro

I first came across X-Ray Spex in the mid-90s, in a Sam Goody dollar CD bin in the 5th Avenue Mall in Anchorage, AK. It was a compilation called Obsessed With You – The Early Years, and every song started with lead singer Poly Styrene’s commanding voice counting in the band. When Styrene (AKA Marianne Joan Elliott-Said) passed away in 2011, I made a small tribute to her by using the sound of her counting to make a realization of Philip Glass’ 1+1. In 2018, I started conceiving a live performance of this Styrene/Glass pairing, which eventually became Count In. While this version is still indebted to the voice of Poly Styrene, it veers away from Glass and toward the compositional techniques of fellow musical minimalists Steve Reich and La Monte Young. In Count In, 8 loops of Styrene’s counting are tuned to the same microtonal lattice that La Monte Young used for The Well-Tuned Piano causing the loops to phase in a similar way to Reich’s early tape pieces.

In this work, I use these techniques of musical minimalism to encourage audiences to experience the work as presence, rather than a present that has been marketed to them. In his book Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time, and Everyday Life, Henri Lefebvre differentiates between presence and the present as such:

Presence is here (and not up there or over there). With presence there is dialogue, the use of time, speech and action. With the present, which is there, there is only exchange and the acceptance of exchange, of the displacement (of the self and the other) by a product, by a simulacrum. The present is a fact and an effect of commerce; while presence situates itself in the poetic: value, creation, situation in the world and not only in the relations of exchange.

Lefebvre connects presence to an awareness that the current moment is part of a larger continuum in time, rather than a frozen, isolated present existing outside of time. The unwavering focus and gradual changes of Count In draw attention to the passage of time, and I hope this awareness inspires audiences to seek out more presence in their lives.

Media and Drama

Count In is a video piece that slowly unfolds over 32 minutes. The sectional changes in Count In are very slow and for many audience members an awareness of time becomes part of the experience. The very idea of 32 contiguous, uninterrupted minutes can be either revelatory or revolting for generations raised on fragmented media experiences.

Whether in Hollywood films or in the 5 seconds we all wait on YouTube before clicking “Skip Ad,” every fragmented pixel of media we engage with is saturated with memetic Trojan Horses meant to push an image, a lifestyle, or a product into your subconscious. When most of us die, a parade of McDonalds radio jingles, Coca-Cola billboards, and Geico TV ads will flash before our eyes, intermingled with memories of family and loved ones. They’re already etched on our frontal lobes, and will provide the commercial breaks as we are rocketed into whatever comes next.

I frame my piece Count In in opposition to this memetic onslaught. I hope that it acts as a mental palate cleanser – a block of time and space that doesn’t have an emotional agenda to sell. During the 32 minutes of the piece, all audiences have to do is watch and listen to numbers and colors as they change. Audiences supply their own narrative based on whatever is in their own heads and hearts. This approach is inspired by something James Tenney said to Gayle Young regarding his Postal Pieces:

Those pieces… involve a very high degree of predictability. If the audience can just believe it after they’ve heard the first twenty seconds of the piece, they can almost determine what’s going to happen the whole rest of the time… When they know that’s the case, they don’t have to worry about it anymore… What they can do is begin to really listen to the sounds, get inside them, notice the details, and consider or meditate on the overall shape of the piece, simple as it may be… Some are angry about it, because they expect and demand meaningful drama. But if you can relax that demand and say ‘no, this is not drama, this is just ‘change’ (LAUGHS) – then you can listen to the sounds for themselves rather than in relation to what proceeded or what will follow” (Garland and Polansky).

I think of the act of listening to change (rather than drama) as an entry point to experiencing presence as Lefebvre defines it. When I invoke these ideas of presence and change vs. drama, it is just as much a reminder for myself as it is a wider cultural commentary. I often find myself lost in the media landscape of the present, drifting away from my own presence. Count In offers little-to-no drama, and thus asks to be experienced as change instead.

This is also true for me when I perform the piece. Count In was originally conceived as a live solo performance, and even the standalone video of it is a screen-recording of a performance. When I perform Count In live, I stand facing the projected screen with a MIDI controller in my hands. It is not a virtuosic performance, as I only trigger a change approximately every 30 seconds. However, variations in microtiming caused by manually triggering changes make every performance slightly different.

After I finished Count In, I found myself asking whether a presentation of Count In requires a live performer, or if a fixed media version expresses the human presence behind the scenes. I have yet to decide on the answer to this, but I have performed Count In live several times now and the standalone video has been shown at venues like REDCAT. Thus far, whether I have been present as a performer or not has depended on logistical concerns much more than how a live performer promotes the audience’s perception of presence and change. For this reason, I have relied more on structural elements of the piece to convey those ideas: form, numbers and colors, microtonality, and rhythm.

Form

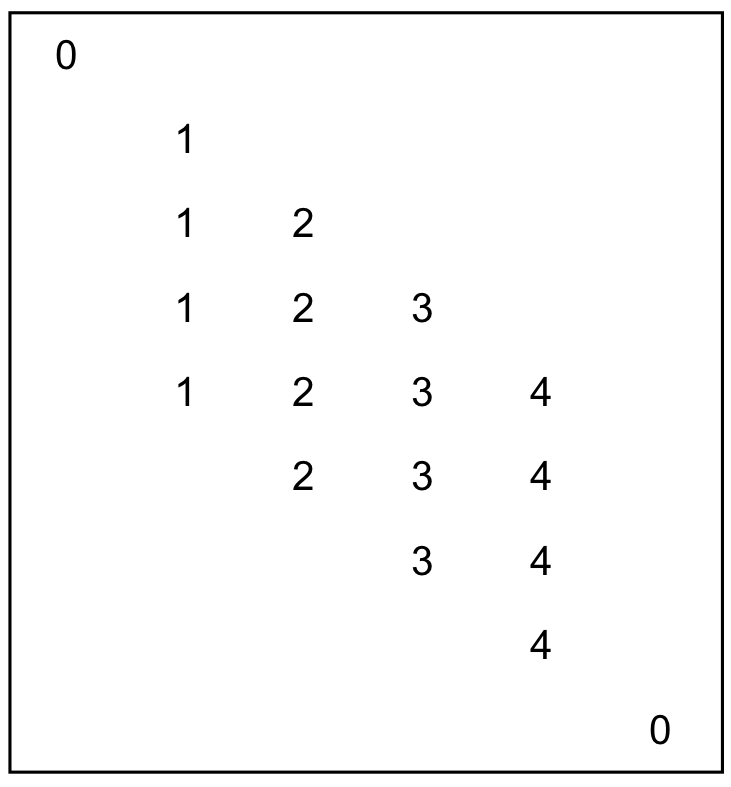

The surface-level form of Count In is simple: 8 loops (represented sonically and visually) all undergo an identical process, shown in Figure 1. This figure should be read left to right and row by row from top to bottom. Each row shows what numbers are within the 8 loops at various parts of the form. There is no activity during the zeros. After that, the loops contain 1, 1-2, 1-2-3, 1-2-3-4, 2-3-4, 3-4, and 4. The piece ends when the loops all return to zero.

Stephen “Lucky” Mosko said half-jokingly in an interview that there are really only 2 musical forms: A-B and A-B-A. In other words, music either travels from one place to another, or it goes somewhere and comes back. Count In plays with this notion by having both A-B and A-B-A forms. The progression from 1 to 4 is a clear A-B form. The 2 formal processes (first adding a number at the end of the loop, then subtracting a number from the beginning) reveal an A-B form as well. However, the results of the additive and subtractive processes shown in Fig. 1 reveal an A-B-A form. Fig. 4 shows how the 1-2-3 sections and the 2-3-4 sections are close to the same length, as are the 1-2 and 3-4 sections and the 1 and 4 sections.

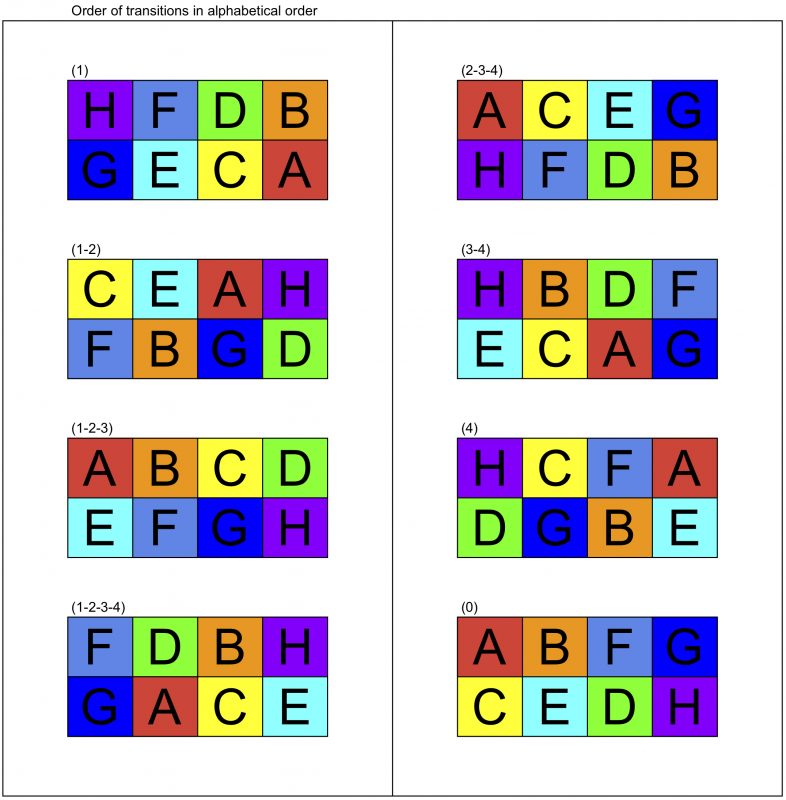

In the visuals for Count In, the 8 numbers are arranged in 2 rows of 4. One of the 8 numbers changes every 30 seconds, and all 8 numbers change before any single number changes again. So, all of the zeros change to 1 before any of them change to 1-2, all of the numbers change to 1-2 before any move on to 1-2-3, etc. In this way, the 8 numbers move in parallel through the piece. However, the order in which the numbers change is different for every transition. There is no immediately perceptible hierarchy to the order, which invites audiences to perceive each transition as a change rather than as drama.

These simple permutations were inspired by Sol Lewitt’s work like Lines in Four Directions. Lewitt’s piece consists of four squares, each of which contains a field of lines in one of four directions: vertical, horizontal, ascending diagonal, or descending diagonal. As I considered the visual element for Count In, I continued looking towards conceptual and minimalist visual art.

Numbers and Colors

In 2006, stop-motion animation legends the Brothers Quay gave their first US talk at the Samuel Goldwyn theater in Beverly Hills. During the talk, they mentioned how the magic of their stop-motion characters only really blooms when those characters are 30 feet tall. The onscreen numbers of Count In are similar in that the abstract shapes of the Arabic numerals are highlighted by greater scale.

When I told my typographer cousin that I used the Calibri typeface for Count In, I could hear the shudder across Facebook Messenger – Calibri has been the default typeface for Microsoft Office since 2007. I made this decision because the typeface is so generic that it doesn’t draw much attention to itself. The numbers in Calibri are monospaced (all the same width), which works well with the way Count In is programmed. In addition, the overlapping stems, serifs, bowls, and crossbars interact to create interesting abstract shapes. I hope the graphic designers of the world will forgive me.

Throughout Count In, all 8 numbers are the same color as each other and change in tandem. Though they change individually in other ways, the monolithic color guides the audiences to perceive the numbers as parts of a single entity. This entity’s color changes through an automated process, in which the Red, Blue, and Green values of the numbers’ tint move individually and very slowly. This makes their change just barely perceptible and non-dramatic — instead becoming almost hypnotic.

The Red, Green, and Blue values each gradually change from 0 to 100% and back again over 42.423 sec, 52.525 sec, and 48.488 respectively. When each color returns to 0, it immediately repeats the same cycle. The changes are slow enough that the full durations of the loops are not perceptible and it takes longer than the length of Count In for all 3 loops to perfectly align. These slow loops interact chaotically, creating seemingly-unpredictable tints that encourage the audience to perceive them as change rather than linear drama.

Tuning

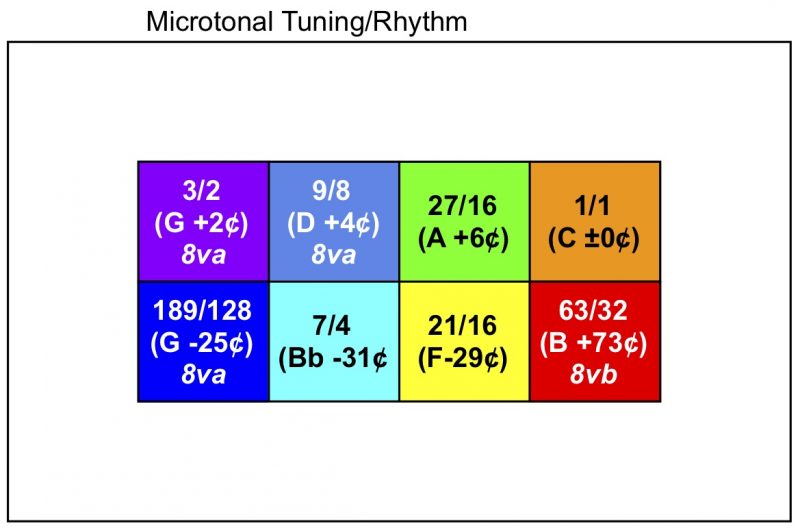

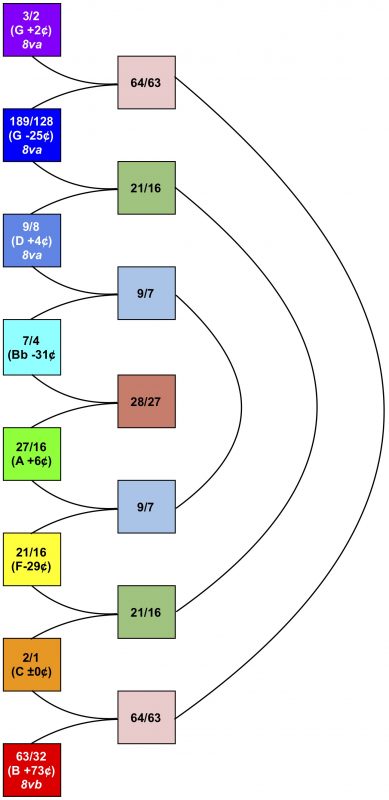

The sound of Count In consists of 8 loops of the same recording played at different speeds. The faster the loop plays, the higher the pitch goes. Figure 4 shows the relationships of all of the loops compared to the 1/1 in orange. The squares in Fig. 4 that have white text are either an octave higher or an octave lower than the written interval. The highest-pitched loop in Count In (the 3/2) is identical to Poly Styrene’s original recording. All other loops are lower and slower. I’ll use these ratios to refer to each position from here on.

Once all of the loops have started, the pitch material is basically the same throughout the piece until the loops stop. It seems that that pitch material should be interesting enough that someone might want to listen to it for 32 minutes. With this in mind, I looked to La Monte Young’s Well Tuned Piano for inspiration. The piano used for WTP is re-tuned in a 2D lattice of 3/2 ratios against 7/4 ratios (Gann). The 8 loops in Count In are tuned to this same grid.

The lowest note is the 63/32 in red. It is 8vb, so it is only 27¢ lower than the 1/1. After that, the next highest note is the 21/16 in the next column (471¢ higher than the 1/1), etc. Since the duration of the loop gets shorter as the audible pitch gets higher, these ratios are rhythmic relations as well as harmonic intervals. 21 repetitions of the 21/16 is the same length as 16 repetitions of the 1/1, which is the same length as 28 repetitions of the 7/4.

My selection and voicing of 8 notes from the 3/2 x 7/4 lattice creates a symmetrical harmony, shown in Figure 5.

The symmetry of this harmonic scheme is challenged by the voice of Styrene, who shouts the numbers rather than singing them. The words aren’t meant to be heard as distinct pitches, and slide up and down as human voices often do – especially when she says “Four.” This gives the harmony some of what Morton Feldman referred to as “disproportionate symmetry,” in which the concept might be symmetrical but its execution is decidedly not.

These harmonic relationships also translate to rhythmic relationships. Notice that the interval between the highest two notes is 64/63 (27.3¢) and the lowest two notes have the same 64/63 interval between them. In addition, the middle two notes (the 27/16 and 7/4) are separated by an interval of 28/27 (63¢). When these small intervals are translated to rhythmic relations, they create phasing patterns roughly akin to early Reich tape pieces.

Rhythm

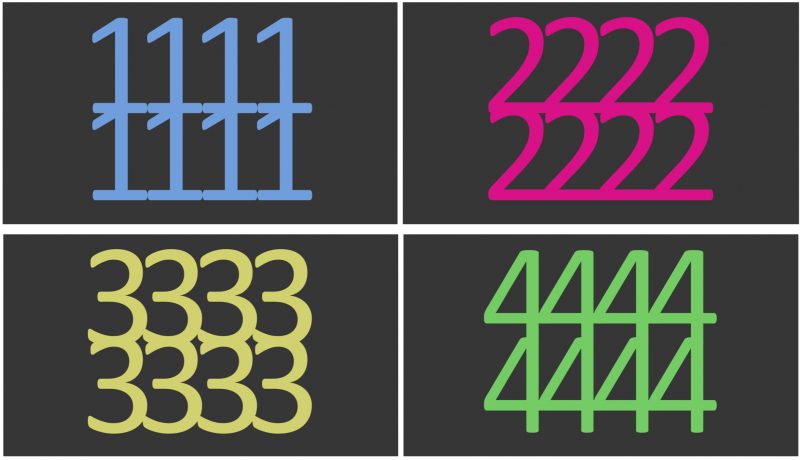

In each section of Count In, a different excerpt of the recording is looped. The recording is divided into 4 near-equal parts, and each part starts with the sound of a number – One, Two, Three, and Four. The length of the original sample is 1312 milliseconds. If the duration of 1312 ms. were divided equally, each number would have a duration of exactly 328 ms. Thus, 1 and 4 would have a duration of 328 ms, 1-2 and 3-4 would have a duration of 656 ms, 1-2-3 and 2-3-4 would have a duration of 984 ms, and 1-2-3-4 would be the full length of 1312 ms. However, the subtle microtiming in Poly Styrene’s counting leads to each of the 4 numbers starting at slightly different times.

Rather than quantize Poly Styrene’s voice to even out these rhythms, I adjusted the length of each number to match her timing. 1 necessarily starts at 0 ms, 2 starts at 345 ms, 3 starts and 661 ms, and 4 starts and 979 ms. Thus, 1 and 4 are slightly different durations, as are 1-2 and 3-4, 1-2-3 and 2-3-4, and 2-3 and 3-4. This microtiming hopefully brings the piece a little further away from mechanical precision and gives these loops a subtle feeling of human embodiment. These deviations from mechanistic timing are amplified by the fact that I manually control each number’s progression through the form described above.

The polyrhythms in Count In are so dense that most audiences have little choice but to experience them as change. Microtiming within these polyrhythms reveals that Count In came out of embodied experiences – Poly Styrene’s, and separately, my own. Embodiment is a key part of rhythmanalysis, which informs Lefebvre’s notion of presence. In her book What is Rhythmanalysis?, Dawn Lyons supports Lefebvre’s ideas about embodiment, but takes issue with how his writing ignores gendered experience and existing feminist literature on the topic. She ultimately states that Lefebvre’s rhythmanalytical approach is worth further exploration regardless of these blind spots, but it is a helpful reminder that these blind spots do exist.

Gender

As I made Count In, I tried to be mindful of the fact that I was using a recording of a woman’s voice as source material. It was a long time ago, but I believe that hearing the X-Ray Spex song “Oh Bondage! Up Yours!” as a teenager was my first awareness of an explicitly feminist perspective. The culture of most of Alaska is quite patriarchal, and it was a surprise to hear such a contrary viewpoint being so powerfully expressed. It also helped me to realize that not everything I have to say is entirely derived from masculinity.

Count In blends “masculine” and “feminine” aesthetics by combining the non-dramatic formal reductions of Tenney’s Postal Pieces with the linguistic dissection of writer Christine Wertheim. Neither artist’s work can really be coded as strictly masculine or feminine, as both draw from influences from either side of this duality. Tenney’s Postal Pieces were musical scores on postcards that were written between 1965 and 1971. During and preceding this time, Tenney was an active participant in Fluxus performances and had been married to “feminist visionary” Carolee Schneemann for 13 years – a marriage that Schneemann later recalled as “equitable” and a mutually respectful partnership between artists (Smigel). One might even attribute Tenney’s later work with musical perception and the physicality of listening to the influence of Schneemann’s body-centric performances, which Tenney often participated in.

In Wertheim’s book +|’me’S-pace, she transforms simple words visually and orally, often through repetition and gradual transformative processes. The word “Time” becomes “+|me” which becomes “| + me,” which becomes “I + me + I + me + …,” marking the “pace” of Time (Wertheim). In her following book mUtter-bAbel, she uses similar transformations to liken the relationship between meaning and language to that between a mother and a son. Wertheim refers to this process as “Litteral Poetics.” The subtitle of +|’me’S-pace is “doc. 001b of the society for cUm|n’ linguistics,” and in Dodie Bellamy’s introduction, she connects it to Valerie Solanas’ SCUM Manifesto. Gender and feminism are prominent topics in Wertheim’s work, which is also evidenced by her work as editor for books like Feminaissance.

In addition, Wertheim was the co-editor of The /n/Oulipian Analects – my own introduction to the Oulipo writing movement. The book grew out of the 2nd noulipo conference, which was held at REDCAT, Los Angeles in 2005. In the first pages of The /n/Oulipian Analects, Julianna Spahr and Stephanie Young in their article “& and” draw attention to the Oulipo movement’s troubling relationship to gender (they also reference Schneemann’s 1964 piece Meat Joy, which Tenney participated in performances of). They posit the creation of a “feminist Oulipo” that they refer to as “foulipo,” which uses writing constraints to draw attention to the embodiment of language. It seems that despite the movement’s gender inequity, Wertheim, co-editor Matias Viegener, Spahr, Young, et al found the legacy of the Oulipo worth devoting a conference and book to. They ultimately take a similar stance to Lyons, saying that there is still something that can be learned from the movement.

The influence of Oulipian constraint-based writing (a movement which produced works explicitly interested in the materiality of text) is clearly present in Count In. The piece explores constrained materials through a clearly defined form (with some entropic elements built in). The transformations of the material make it difficult to identify the sonic source or assign it a gender, and I hope that this ambiguity is sympathetic with the work of Wertheim, Styrene, and Tenney.

Though it’s largely outside of the scope of this writing, it’s also important to note how race plays a part in the identity of Count In. The voice of this woman of Somali and Scottish parentage stands out within the largely whitewashed history of punk, and that resonated with my own experience being half Filipino in the primarily white culture of Anchorage, Alaska. Though these are very different histories, they are each part of a respective presence connected to a diasporic lineage. While Count In isn’t a piece about race, I hope that the sort of presence that Count In inspires includes this sort of consideration.

Closing Thoughts

With Count In, I tried to make a piece that could be experienced as change rather than drama. This was inspired by a personal need to create a block of time and space for presence, without the market incentives of the present. The stark continuity of the piece is a response to the fragmentary way that most people experience media. This fragmentation spills into how we engage with the world, as Andy Warhol describes well in his 1985 book America:

With people only in their public personalities, and with the media only in the Now, we never get the full story about anything. Our role models, the people we admire, the people American children think of as heroes, are all these half-people. So if you have a real life you can get a lot of crazy ideas from this information. You can think you’re a real loser, and you can think if only you were rich or famous or beautiful, your life would be perfect, too.

The media can turn anyone into a half-person, and it can make anyone think that they should try to become a half-person as well.

I hope that Count In, through its form, visuals, tuning, and rhythm invites audiences to be aware of their own embodied experience of time.

Bibliography

“Encounter Two: Lefebvre and Blanchot.” Artmaking in the Age of Global Capitalism: Visual Practices, Philosophy, Politics, by Jan Bryant, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2019, pp. 46–54. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctvrs91hz.13. Accessed 2 Apr. 2021.

Cotter, Holland. “Carolee Schneemann, Visionary Feminist Performance Artist, Dies at 79.” New York Times, 10 Mar. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/03/10/obituaries/carolee-schneemann-dead-at-79.html.

“Crippled Symmetry.” Give My Regards to Eighth Street: Collected Writings of Morton Feldman, by Morton Feldman, Exact Change, 2001, pp. 134–149.

“Postal Pieces.” Soundings 13: the Music of James Tenney, by Peter Garland and Larry Polansky, Soundings Press, 1984, pp. 193–203.

Gann, Kyle. “The Outer Edges of Consonance.” Sound and Light : La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, edited by William Duckworth, 1st ed., vol. 40, Bucknell University Press, 2009, pp. 152–190. Bucknell Review.

Laws, Catherine. “Embodiment and Gesture in Performance: Practice-Led Perspectives.” Artistic Experimentation in Music: An Anthology, edited by Darla Crispin and Bob Gilmore, Leuven University Press, Leuven (Belgium), 2014, pp. 131–142. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt14jxsmx.16. Accessed 9 Apr. 2021.

Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time, and Everyday Life, by Henri Lefebvre, Bloomsbury Academic, an Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing PIc, 2017, p. 56.

Lyon, Dawn. What is Rhythmanalysis?. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 9 Apr. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350018310>.

Scarpelli, DC. “Introduction to Typography.” 2020.

Smigle, Eric. “”to Behold with Wonder”: Theory, Theater, and the Collaboration of James Tenney and Carolee Schneemann.” Journal of the Society for American Music 11.1 (2017): 1-24. ProQuest. Web. 11 May 2021.

Warhol, Andy. America, Harper & Row, New York, NY, 1985, pp. 24–87.

Wertheim, Christine. Feminaissance. Les Figues Press, 2010.

Wertheim, Christine. MUtter–BAbel. Counterpath, 2014.

Wertheim, Christine, and Matias Viegener. The Noulipian Analects. Les Figues Press, 2007.

Wertheim, Christine. +I’me’s-Pace: an Examination of the English Tongue from the Viewpoint of Poetry. Les Figues Press, 2007.

Recordings

X-Ray Spex. Obsessed With You – The Early Years.

More from this issue