In 1952, as Walt Disney was seeking a location for his amusement park, he hired a consultant named Harrison “Buzz” Price from the Stanford Research Institute to determine the most viable and cost-efficient plottage in the vicinity of Los Angeles. Price pointed to a 160-acre enclave of orange groves and walnut trees in Anaheim, just south of the Santa Ana mountains in nearby Orange County, hardly a destination at the time. A relatively sleepy town, Anaheim had been founded in the mid-nineteenth century by a group of Bavarian-Jewish immigrants as vineland, and the town was a major wine exporter until the Prohibition — by 1955, the former farmland was being razed to make way for Disneyland. At the center of the park the now-iconic Sleeping Beauty’s Castle was erected, a structure that imagineer Marvin Davis had implausibly modelled after the Neuschwagstein, Ludwig II’s monument to Richard Wagner. Later, in 1983 — as Ronald Reagan, who had served as a master of ceremonies for the Disneyland opening ceremony, sat in the White House—the entirety of Fantasyland was renovated to resemble a Bavarian village.

°o°

Disney is low-hanging fruit. In cultural criticism, it is offered as shorthand for post-war American hegemony, a through-line that spans Theodor Adorno’s warning that the sadomasochism of Donald Duck cartoons were psychic preparation for totalitarian violence, to the theme park’s Main Street U.S.A. as ur-text of Baudrillardian hyper-reality, to schoolyard conspiracy theories about subliminal messaging, cryogenic freezing, and crypto-Nazism. Disney as symbol for the sinister elements of American culture lurking beneath anti-septic exterior seemed extra-prescient in the era of Michael Eisner, who saved the Walt Disney Company by transforming it into a hydra-headed media conglomerate. From his 1984 CEO election-by-greenmail to his unceremonious resignation-by-shareholder-coup in 2005, Eisner presided over Disney’s global expansion, its purchases of ABC, ESPN, and Miramax, and the revitalization of its animation studio via parade of multicultural titles (even as the company maintained suspect global labor practices, consistently ranking as one of the top 10 worst companies by the Multinational Monitor throughout the ‘90s).

The Disney Company now seems to be bracing for a new Disney Decade, swooping up Marvel and Lucasfilms holdings in anticipation of its new billion-dollar proprietary streaming service Disney+ and churning out high-definition reimaginings of its golden era productions at an alarming rate (live-action editions of The Lion King, Dumbo, Aladdin, and Lady and the Tramp due by 2020, and Mulan and Pinocchio around the corner). This fall in Chelsea, New York, the company unveiled a 16,000 square-foot pop-up exhibition titled Mickey: The True Original, overseen by former Scooter Braun creative director Darren Romanelli (DRx) and featuring Mickey-inspired work by one-time Merce Cunningham set designer Daniel Arsham, ‘80s East Village denizen Kenny Scharf, Japanese pop-artist Keiichi Tanaami, installation artist Shinique Smith, and so on. Commemorating the 90th anniversary of the character, the centerpiece is a multi-style reanimated Steamboat Willie, a title once thought to be so sacred the company made copyright extension lobbying a core of its mission in order to defer its addition to the public domain.

Rarely has a corporation invested as much in the representation of its history. Even in an age of celebrity CEOs and self-entrepreneurship, Walt Disney is hardly matched in visibility, from the Willy Wonka-like dispatches of The Reluctant Dragon or The Wonderful World of Disney to his propensity to walk around his parks and shake children’s hands. Few if any other companies have developed their own hall-of-fame system for employees (a.k.a. “imagineers”), the Disney Legends that greet visitors to the Walt Disney Studios. So self-contained is the world of Disney that it has its own cultural memory, its own canon. The Nine Old Men are its old masters, and the Disney Princesses are its great works.

In the mid-to-late-’00s, Disney’s Pixar was offering a burst of Obama-lite hope with its Silicon-Valley-iodine roster of new properties like Up and WALL-E—but now it seems we should be bracing ourselves for an era of lifeless CGI-recast remakes and Mickey Mouse centennials. This would be less mind-numbing if the company seemed remotely interested in the critical assessment of its history—it was of course the company that invited Leni Riefenstahl to its studios and made Song of the South—rather than using the past as a value-optimization exercise for its holdings. Disney, after all, was the pioneer of artificial-scarcity home video marketing, in the early days selling VHS tapes of Pinocchio for $90 a pop and goading parents that if they did not act quick, its titles would fall back into the Disney Vault. In the world of vertical integration and content saturation, the emphasis is placed not on the properties’ inherent value but their malleability, their ability to be merchandised, or on speculation for their ability to ooze into niche markets.

That Mickey: The True Original is taking place down the street from the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Andy Warhol retrospective — and that Andy Warhol’s Mickey Mouse quadrant was commemorated on limited-edition Uniqlo UT apparel in its honor — is unsurprising enough. Disney the floating global media empire is like the funhouse mirror of our museums, concert halls, and alternative arts spaces, whose activities have turned increasingly into a similar sort of retrospective-ouroboros. Even as these venues imagine themselves enclaves from amusement-park consumer monoculture, how does the glut of the contemporary art-institutional experience not feel thoroughly Disneyfied? Thematized floors and membership cards, 180-gram vinyl reissues and animatronic rehashings of historical happenings, the constant threat of works getting thrown back into the Disney Vault, a pantheon of art-stars no less arbitrary than the Legends in Burbank. The contemporary arts in the United States, like Disneyland, were devised in a post-war utopian imaginary — and, inevitably, they were both built in the shadow of a 5/8th-scale ersatz Neuschwagstein.

°o°

The Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Walt Disney Concert Hall is in the midst of hosting a gargantuan retrospective of Fluxus composition, likely the most coordinated musical survey of Fluxus in the United States.

The Walt Disney Company has no formal stake in the concert hall aside from being a reliable overseer-donor to the Los Angeles Philharmonic — not to mention Jane B. Eisner, wife of Michael, sits on the board — though certainly the magic rubs off by association. Immediately recognizable by its large metallic curvature, the Walt Disney Concert Hall was designed by Frank Gehry using CATIA, an aerospace design software package that had been used by Dassault for Mirage fighter jets. To its rear, Gehry installed an uncharacteristically saccharine fountain made of blue china shards titled A Rose for Lilly, in commemoration of Walt’s widow. Lillian Disney had initiated the hall’s construction with a $50 million gift in 1987, later bolstered with a finish-line $25 million gift from the Walt Disney Company a decade later. The hall was completed at the turn of the millenium and the Philharmonic took residence in October 2003, inaugurated by a gala that began with The Star-Spangled Banner and ended with The Rite of Spring, the Philharmonic’s signature work.

The Los Angeles Philharmonic has positioned itself as the most forward-thinking and financially-solvent classical musical entity in the country. At a time in which the field of classical music is struggling to reckon with its white-male dominant history, the Philharmonic has done consistently better than other orchestras at commissioning women and composers of color, establishing annual diversity fellowships and tackling gender imbalance of conductors. A part of the Phil’s diversity initiative has been broadening the scope of the orchestra, and its recent programming has sought to balance European canon with Frank Zappa, Herbie Hancock, Katy Perry, and Kali Uchis, along with the Hollywood scores and the pet West Coast post-minimalists that have distinguished the Philharmonic’s sound and identity.

For these reasons, the Fluxus program seems to follow as an extension of the Philharmonic’s “multidisciplinary” and “innovative”-minded programming. These words, vague and progressive-seeming, make Fluxus and Disney seem like strange bedfellows. One of Walt Disney’s long-held dreams was to create an interdisciplinary university (a “Seven Arts City”) modelled after Bauhaus, and it came into fruition three years after his death as CalArts. The faculty, recruited by its president Robert W. Corrigan and its dean, performance theorist Herbert Blau, drew in several Fluxus participants including Nam June Paik, Allan Kaprow, and Alison Knowles. The American participants of Fluxus were largely born middle- or upper-class between 1930 and 1940, which is to say the initial cohort of children who grew up with Disney’s first golden-age features, and so it seems fitting that thirty years later some of them would get Disneyland Golden Passes as a side perk for their arts professorships.

George Maciunas, the coiner of the word Fluxus and its chief ideological fount, emigrated to Long Island as a teenager in 1948. At Cooper Union and New York University, he was schooled in architecture, graphic design, and art history, which fed into a fixation on mapping a taxonomy of the avant-garde, leading him to correspond with participants in Dada. His interest in vanguard art — initially, to him, pre-war avant-garde, Soviet socialist-realism, and the Columbia-Princeton composers — brought him in contact with a number of young artists and composers deep in their own formal exercises. He caught wind of John Cage’s experimental music composition course at the New School (although he did not participate himself) and attended La Monte Young and Yoko Ono’s Chamber Street loft concerts. His early organizing efforts were reliant on these existing energies, which spouted from radical composition, experimental poetry, and the fringes of the art world; Fluxus, whose structure brings to mind a gamified corporate bureaucracy, a parody of art discourse, or a dysfunctional political organization, came out of this milieu.

In a series of diagrams outlining the historical development of Fluxus and the expanded arts, Maciunas locates the impetus for the ‘movement’ in neo-dada, junk art, Futurism, Byzantine iconoclasm, the Gutai group, Wagnerism — and Walt Disney spectacles. (Later, in a diagram published in Film Culture, he chalks up the entirety of expanded cinema to Disney.) What Maciunas saw in Disney was the mystification of the new—to use Maciunas’s word, “pseudotechnology.” Maciunas was resigned about the relationship between art and technology, critiquing the artist as rationalist; his interests drifted towards useless or self-abortive mechanics. Maciunas admired vaudeville and had a particularly fondness for Spike Jones and his City Slickers. Self-destructing instruments, sight gags, Rube-Goldberg machines — these were Maciunas’ priorities, a fact which frustrated many of the artists he invited to join Fluxus.

Maciunas must have watched Disney’s TV broadcasts — his Walt Disney’s Disneyland dispatches on ABC or his stagey ‘demonstrations’ of animation technique on Walt Disney Presents — from his Great Neck TV with great interest. Disney and Maciunas’ conception of the uses of technological spectacle came from different side of the tracks, granted. Disney’s intermedia was productive, a gee-whiz spectacle; Maciunas and many of his cohort imported a neo-Dada nihilism or a political critique of the art institution into their work. Disney made no attempt to hide his jingoism and had been a pivotal Hollywood anti-communist, monitoring his animation studios for dissidents and squashing organizing efforts, at one point offering Disneyland as a covert operations headquarter for the FBI; Maciunas was nominally involved in left-wing causes, and in the early ‘60s had attempted to make contact with Soviet culture ministries to discuss offering Fluxus as an official cultural program.

However, the overlap between the two is palpable. As Maciunas’s organizing efforts took increasingly extreme form (at one point, he attempted to acquire an island for Fluxus), his most auspicious contribution became the row of artist co-ops he developed in SoHo known as the Fluxhouse Cooperatives. Disney began to see his own amusement park forays as an essential failure and became fixated on his Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (EPCOT), a twenty-thousand person community he intended to house in Disneyland East, a model for a self-sufficient global community he intended to develop and market. Even with their vanguardist aspirations, both saw themselves as ultimately anti-elitist figures advocating for a neutral, post-national identity — and so, in their wake, Maciunas has left the shopping district SoHo and Disney the post-modern planned community Celebration, Florida.

The edge-skating total theatre-work of the post-war avant-garde, too, when backed away from can seem like a Disney light show — especially with the benefit of hindsight, as its political gestures seem quixotic or worse. In fact, the dismal “Baroque Hoedown” theme that accompanies Disneyland’s Main Street Electrical Parade was composed by Gershon Kingsley, a one-time student of John Cage and an acquaintance of La Monte Young. During the Eisner era, as Disneyland was expanding to Paris, its vice president Jean-Luc Choplin was recruited from the arts and had a previous stint as the director of the Fêtes musicales de la Saint Baume from 1976 to 1980, developing what he called an “interdisciplinary laboratory” and working with artists including John Cage, Yvonne Rainer, and Takehisa Kosugi.

°o°

Los Angeles’s cultural character has always depended on its contradictions. An interwar emigration haven — counted among its musical ex-pats were Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, Ernest Toch, Edgard Varèse, Theodor Adorno, Hanns Eisler, and so on — and yet the headquarters of the culture industry, its frontier mythos meets spiritualist undercurrent, its haughty ranchero style meets po-mo architecture. It was therefore fertile soil for the American maverick composer style: where Henry Cowell founded his New Music Society in 1925 (he later uprooted it to north), and Harry Partch, then an usher for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, had his torrid affair with Ramón Novarro, MGM’s “Latin lover.” John Cage, the son of an inventor, would pass Aimee Semple McPherson’s Angelus Church on his way to Los Angeles High School, and La Monte Young beat out Eric Dolphy for second-chair saxophone at Los Angeles City College — or so go the Parsifal legends.

There was a time when renegade composers, frustrated with the stand-still pace of American concert music, saw in the Hollywood studio system a glimmer of opportunity for an emerging artform. In the ‘30s, competitive pay rates and plentiful jobs (each studio nursed its own 45-musician orchestra) meant a stead of skilled instrumentalists and adventurous composers venturing to Los Angeles, and music departments were rapidly expanding. George Antheil was one such intrepid traveller, coming to the West coast first under the auspices of writing an experimental opera about the Southwest. The son of a shoe-maker from Teaneck, New Jersey, Antheil had cultivated the reputation of rogue Yankee modernist, consorting in the Parisian intelligentsia of the ’20s (including Ezra Pound, who suggested he was the only American composer worth taking seriously) and fancying himself an inheritor of a new American-variant Futurism. He worked with Fernand Léger, Man Ray, and Dudley Moore on the early abstract film Ballet Mécanique — though they mutually decided to split the score and film into two distinct works. He cultivated a cowboy image, promoting riots and fist fights at premieres and keeping a loaded gun on person during concerts. His hustle might have impressed Europeans, but the New York debut of Ballet Mécanique, advertised on midtown billboards, flopped. Cash-strapped, Antheil moved to Los Angeles full-time in 1936 with the ambition of becoming a score composer, finding modest income as a columnist on industry news for the League of Composers’ Modern Music.

Antheil’s hopes for screen music were based on the promise that it would offer new opportunities for young high-minded composers. He felt the largest obstacle to be the studio system’s “afterward” method of scoring, which gave composers three weeks to orchestrate soundtracks for completed pictures. This not only lead to rushed scores, but also a simplistic, representational style that promoted a facile relationship between image and sound. This problem was abated by animation, which he understood to be a novel artform, an advancement of the ideas he had attempted with the Surrealists two decades prior; Mickey Mouse shorts, he concluded, “were operas in the purest sense of the word.” Antheil was thus up in arms with news that Leopold Stokowski, the musical director of the Philadelphia Orchestra, had come to Los Angeles on contract to potentially develop a Richard Wagner biopic and had run into Walt Disney at West Hollywood restaurant Chasen’s. Industry-guided rumors sprinkle Antheil’s On the Hollywood Front columns, written between 1936 and 1939 before he abandoned the position. The most outlandish was the speculation that Stokowski was developing an “electronic orchestra” for the film’s climax, a claim rooted in the truth that Disney and Stokowski had been meeting with RCA to develop Fantasound, the most comprehensive multi-channel sound system of its type.

The production of Disney’s Fantasia was intended to be Walt Disney’s rehabilitation of the Mickey character, whose popularity the animator feared was beginning to wane. It was an ambitious undertaking for Disney — a man who always considered himself a middle-American dilettante offering a populist alternative to elite coastal culture — to partner with the lauded figures of classical music, stepping into the shoes of a populizer. The concept was a novelty for the film industry, which despite having been staffed by European emigrants who had been trained in Viennese opera and Mahler in their home countries had rarely done literal interpretation of concert music, and thus the studio enlisted the input of modernist literati — including Thomas Mann who looked over storyboards for the Mickey Mouse segment and pointed out to Disney that Paul Luckas’s work was based on Goethe’s Der Zauberlherling. In the early stages of production, Walt Disney sought out Oskar Fischinger, the German abstract animator, and put him on contract with the intention of letting him lead an entire segment (none of his work was used in Fantasia, although he did develop practical effects in Pinocchio). During this time a young John Cage apprenticed for Fischinger, crediting his work as a major impetus for his early percussion compositions.

Released in 1940 as a 50-city travelling road show that installed temporary surround-sound speakers into concert halls and pavilions across the country, Fantasia was a moderate success, although it was systemically derided by film critics and composers. Igor Stravinsky, who had been initially pleased by his inclusion and found the storyboards for the Rite of Spring passage to be fitting, felt the film neutered its musical material. In an infamous review by Dorothy Thompson in The New York Herald, the critic described it as “brutal and brutalizing,” a “caricature of the Decline of the West;” Paul Bowles, who took over George Antheil’s column in 1940, called it “the perfect Fascist entertainment.”

Within two years, Disney’s emphasis would have to dramatically shift away from large-scale productions like Fantasia — and in fact, Hollywood studio music’s technological development suffered greatly during this time. Beginning in 1942, Walt Disney Productions was contracted by the United States government to develop propaganda and training videos for every division of the U.S. military, a task which occupied 90% of their animation team. Ironically, in George Antheil’s final 1939 On the Hollywood Front column, he suggested that war-time would be beneficial for “serious minded composers” as studios would be “clamoring for a series of ‘ultra-modern’ (whatever that means!) scores,” a hunch that turned out to be entirely wrong as he found himself out of work for four years. It gave him the time to focus on his other passions — amateur criminology and endocrinology — the latter of which put him in contact with actress Hedy Lamar, who was soliciting advice to improve her figure. In 1941, Antheil and Lamar developed a system of broadcast interference to disrupt torpedo flight patterns, thought up by the two of them one evening while sitting at Antheil’s piano.

°o°

Though Fantasia garnered mixed response from the contemporary music establishment and its technical achievements were abandoned in wartime, its sixty-speaker surround-sound system made a significant splash in electroacoustic composition years later. Then living in Los Angeles, Edgard Varèse used a nearly identical spatial technique in 1958’s Poèmes électronique (six years prior he had attempted to court Disney’s interest in a preliminary version of Déserts). Certainly it had captured the attention of Karlheinz Stockhausen, who became fixated on spatialized loudspeaker work between 1958-1960 — Carré, developed while in the United States and fleshed out by assistant Cornelius Cardew, seemed to develop out of both the mechanics of Fantasound and Leopold Stokowski’s writing on orchestral tone, color, and space.

Karlheinz Stockhausen was first brought to North America in 1958 by Leonard Stein, Arnold Schoenberg’s one-time assistant, and Lawrence Morton, a concert organizer who had taken over George Antheil’s former column from Paul Bowles. Morton was similar to Antheil in that he came to Hollywood as an arranger and composer. Morton had taken over Peter Yates’ position as the director of the Evenings on the Roof (renamed Monday Evening Concerts under Morton), a weekly chamber concert series of classical repertoire and the avant-garde that had initially enlisted film studio instrumentalists. Morton had taken the series into an increasingly Euro-modernist direction, advocating for the European avant-garde of Pierre Boulez, Luigi Nono, and Luciano Berio.

At Stein and Morton’s behest, Stockhausen did a rapid-fire series of large university engagements across the United States and Canada, crediting the long intermittent flights as the foundation for Carré’s temporal shifts (he made notes for Cardew to sort out later). Hardly having left Germany in his youth, Stockhausen was most struck by his time in New York, which he described in his personal writing as “the first model for a global society” and “unquestionably an indensable experience for a contemporary artist.” He socialized with Robert Rauschenberg, whose social circle introduced him to Varèse, Partch, Gunther Schuller, Morton Feldman, Milton Babbitt, and more — subsequently, he got into the habit of visiting often, making trips and long stays in the city and Long Island regularly over the next five years. Stockhausen used these visits as study retreat, developing a steady interest in mass media and the prospect of a “global village”; biographer Michael Kurz notes that he spent a whole New York summer studying evolutionary biologist Wolfang Wieser’s 1959 Organismen, Strukturen, Maschisen, an early cybernetic text on the inter-special relationships between organisms. His compositional interests began to follow suit, becoming syncretic exercises in his holist concerns: Disney-ish telematics, one-worldism, and misguided cultural hybridism.

Today Stockhausen exists in the same synecdochal space as Walt Disney, more enterprise than person. He was an avatar for the excesses of serialism, scientism, and German democracy; the poster boy for “decadent capitalist culture,” snipped Shostakovich at one conference; Luigi Nono stopped associating with him on political grounds, likening Stockhausen’s statistical musical structure to the seeds of fascism; in the ‘70s, his former assistant Cardew titled his Maoist critique of experimental music aesthetics Stockhausen Serves Imperialism. Stockhausen’s role as the antagonist to the rising generation of mid-’60s politically-minded generation of composers was significant, the reputation resting on his reliance on state funds, his scientific chauvinism, his treatment of ethnic musical tradition as compositional substance, and his Adorno-inflected dismissal of jazz.

The kerfuffle surrounding the New York premiere of Stockhausen’s Originale, for instance, is often offered as a confrontation between Western art music and an ascending critique of the art institution. In 1963, George Maciunas had begun to assess the failures of Dada as due to its lack of direct political inclinations, and attempted to coordinate the group’s tendencies, suggesting acts of “anti-art terrorism” and an effort to lobby communist parties to advocate for the elimination of art. The following events — his tentative alliance with the young philosopher and ‘anti-art’ agitator Henry Flynt, feuds with Dick Higgins and George Brecht over the organization of rival festivals, his failed attempts to travel to the Soviet Union—blur the line between ‘scene beef,’ political LARP, and institutional critique, culminating with the picket of the Stockhausen piece by Maciunas, Flynt, Takako Saito, and others. The picket line featured signs reading “Stockhausen — ’Patrician Theorist’ of White Supremacy: Go To Hell” and “Fight Musical Racism”; Participants in Stockhausen’s piece were said to have joined, as well as provakateurs such as Allan Ginsberg, giving some press and public the impression that the protest was organized as part of the piece. The fallout found Maciunas expelled from his own organization, and Fluxus — until that point best understood as the excrements of Maciunas’ rapidly evolving ideologies — increasingly fractured, unleashed into self-determination like Frankenstein’s monster.

The broad-stroke, storied afterlife of these events could give the impression that there existed an essential ideological distance between Fluxus and Stockhausen. In fact, during this time Stockhausen was involved with the artist Mary Bauermeister, the daughter of an anthropologist and artist in her own right. Between 1959 and 1960, Bauermeister had been organizing regular concerts at her atelier in Cologne, inviting composers and artists such as Cardew, David Tudor, John Cage, Christo, George Brecht, Ben Patterson, and Nam June Paik for small salon-like audiences — a series that prefigures Fluxus’s inception. Bauermeister was one of several artists Maciunas was corresponding with regarding the organization of international Fluxus fests in the 1963-64 period, and he allegedly felt threatened by her activities.

Stockhausen’s Originale developed from his encounters with the proto-Fluxus Bauermeister performances, and artists such as Jackson Mac Low or Allan Kaprow (both in the piece’s New York realization). Set to his earlier serialist work Kontakte, the piece featured tightly-choreographed action sets carried out by a cast of about 20 performers (and in at least one case, a zoo ape). Developed over a summer holiday in Finland, it was his attempt at total-theatre, an amalgamation of his interests in systems theory, his understanding of Happenings, and even his early experience of Pop Art. Though participants in the protest would later admit that it was not the contents of Originale that they attacked—a more appropriate target could have been produced—it was the principal: Stockhausen was, in Henry Flynt’s estimation, “court music” and “decoration for [the] bosses.”

°o°

The same week as the Judson Hall premiere of Originale, Walt Disney was closing the first phase of a Gesamtkunstwerk of his own less than ten miles away in Flushings, Queens. The New York World’s Fair 1964/1965 was winding down its 1964 season, a 140-pavilion exhibition organized around the theme of “Peace Through Understanding” — an ironic title, given that the Fair’s strategy of charging pavilion rental fees lead to the non-participation of Canada, Australia, most Western allies, and the Soviet Union. The Fair, itself a recapitulation of the half-remembered 1939/1940 iteration, was first and foremost a monument to American industry, with contributions ranging from General Motors’ Futurama tour through futurist domestic consumer goods, to IBM mainframe demos, to a tire-shaped US Royal ferris wheel.

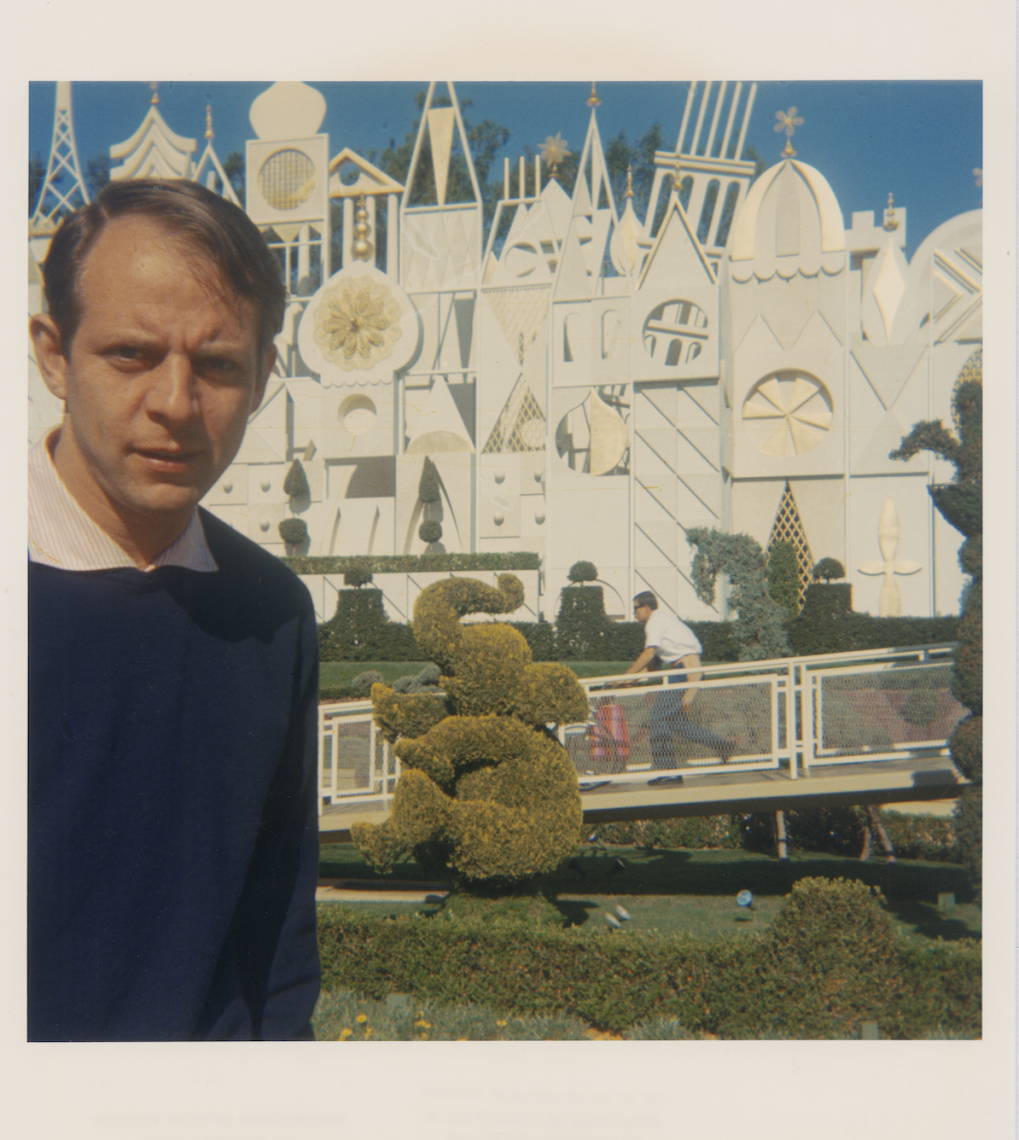

With the aid of consultant Harrison “Buzz” Price, who helped secure brand sponsorships, Walt Disney and WED Enterprises unveiled four large-scale attractions: the Ford Magic Skyway, a trip through prehistoric time in Ford’s new Mustang model; the Carousel of Progress, a demonstration of General Motors’ products using Audio-Animatronics; an animatronic lecture by Abraham Lincoln; and most ambitious, “Pepsi-Cola Presents Disney’s “It’s a Small World” — A Salute to the World’s Children,” a partnership with Pepsi and UNICEF that featured a boat-ride through the nations of the world. A prototype produced in 1962 titled “Children of the World” featured over 80 Audio-Animatronics singing their homeland’s respective national anthems, an idea that resulted in a cacophonous noise. Disney quickly discarded the concept — though the anecdote likely reached the ears of Stockhausen, whose 1966 piece Hymnen features a quadrophonic deconstruction of various anthems.

Disney instead enlisted the songwriting duo Richard and Robert Sherman, the grandchildren of an Austro-Hungarian court composer who had leveraged their music publishing company into dual staff writing positions for Walt Disney Studios. Written in October 1962 in the wake of the Cuban missile crisis — during which George Antheil and Hedy Lamarr’s broadcast interference technology, patent since expired, was apparently put to use—the Sherman brothers sketched the “It’s a Small World” tune that still regales the five Disneyland Fantasylands in Anaheim, Bay Lake, Paris, Tokyo, and Hong Kong as an apparent message of peace and ‘brotherhood.’ It’s no wonder that in 1966, as he worked out the 1967 New York Philharmonic orchestral variation of Hymnen, Stockhausen paid tribute to the attraction on a visit to the park with Betty Freeman.

°o°

Later in life, George Antheil wrote that, for all its faults, Hollywood was at least “an artist colony that works.”

More from this issue