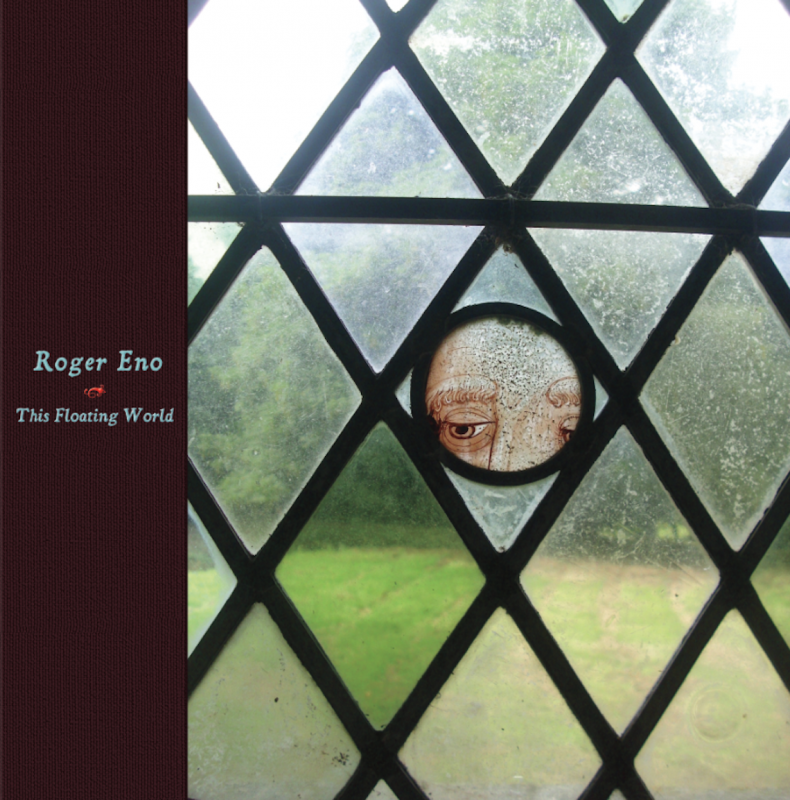

The artistic persona is one tool that is available to composers as classical music continually winnows and diverges. These masks do not cover anything up, so much as look out on an odd landscape that peers back at them. Roger Eno has previously demonstrated in his 1995 album The Music of Neglected English Composers that he is particularly adept at this methodology, the fragmentation and fictionalization of compositional technique. In that album, Eno composed music that he then attributed to a series of fictional, “neglected,” and specifically English composers. The approach allowed him to delve into plausible musical histories for his country — to posit a lineage while also venturing outside his expectations for himself as a composer.

But a rebuff to the method of devising artistic personas arises when one starts to think past the vision of diverse artists and onto, if you will, a cosmic vision. Our world is made of people, their creations and perspectives, and then rocks, and the creatures that live underneath the rocks. The calls of crows and songbirds and the chimes from someone’s house rush in the wind like music.

While Eno’s newest album, This Floating World, does not carry the kind of cosmic message of Messaien or Stockhausen, its constituent piano compositions do create worlds rather than perspectives. In “Dee Dee Alone,” the uncertainty of whether a repeating note will come in at the same, a longer, or a shorter interval, one or two more times before the following chord, has the sense of tenuousness of a young solar system. While listening, new rules become as apparent to us as the natural laws that govern traveling sound in our own world. The pieces seem so simple, stripped-down, and haunting that they reveal new elementary principles.

Within a world, as I’ve said, are individual worldviews, and pausing on one of them can give the impression that an individual perspective has become an entirety. In the 12-page liner notes accompanying the LP, a series of (very) short stories further affirm the idea that a whole world is held within some of our individual experiences. Scattered among the booklet’s stories are uninhabited photographs, taken by the artist, that develop the relationship between our surrounding objects and the narratives winding around them. The wall of a house is built of stones and then left standing, accumulating moss, after the rest of the building has collapsed. In Eno’s style of minimalism, a recurring melody may occasionally seem forgotten before we see that it has been cared for all along (as the wall is observed and eventually photographed). As Eno’s compositions tug out simple interrelations between pitches and chords from one angle at a time, we occasionally even forget where we are headed, inevitably toward the end of the song and record.

An album like this does beg the familiar question of how it all adds up. How could disparate compositions, separate worlds, flow together into a single release? Is this album a harmonious universe, or is it, like ours, slowly splitting at its seams, or even more quickly?

A similar series of questions applies to the cohesion of Sean McCann’s record label, Recital Program, which released This Floating World this November as its 39th release. The label’s grouping of such established luminaries as Loren Conners and Annea Lockwood with younger and distinctly talented composers like Ian William Craig, Karla Borecki, and McCann himself closely resembles Eno’s puzzle of fitting together sonic worlds. Really, the puzzles are the same, and from both arises the solution of open collaboration. The efforts of composers involved with Recital stretch to every reach of the album production process. It is no surprise when emeritus musicians “Blue” Gene Tyranny and Phil Niblock step in to create the liner notes and artwork for the latest release by a young composer, Michael Vincent Waller. Roger Eno may have only recently joined the Recital community, but his latest music floats along with the same spirit of autonomy and convergence in its components; it is imbued with collaboration (which is not to mention his past collaborations with Kate St. John, Lol Hammond, Peter Hammil, Laraaji, and others).

With Sean McCann’s foresight, his label has established a welcoming and mysterious space for a range of creative endeavors. In this space, the past is alive, at times replacing the present and future. An MP3 of a collaborative album by McCann, Graham Lambkin, Madalyn Merkey, Zach Schwartz, and others was recently released for free on the label under the artist name Simple Affections (along with several beautiful postcards –– don’t overlook the importance of visual art for Recital Program) and the last two tracks are named after late 18th-, early 19th-century composers Alexander Scriabin and Camille Saint-Saëns. The pieces –– odes, appropriations, elaborations –– take the composers’ work as a starting point and build an atmosphere out of recorded and produced sounds that again reflect the mentality of those composers.

McCann began publishing tapes in 2007, but it wasn’t until 2012 that he started Recital Program as an effort to create LPs, CDs, and cassettes with a bit more staying power than his previous releases (1). The genesis of Recital allowed McCann to “turn a new page” and reappraise “what is significant and exciting in contemporary music” (2). About six years after that moment, their catalogue has followed that mission precisely. Beyond the spirit of unity itself, one thread that has continued to unify Recital’s releases is experimentation that maintains deep and wide-spreading roots. Neither Eno nor McCann, though, would worry too much about establishing these through-lines because they come naturally with the work.

The electroacoustic tradition is now a musical fact and the question is how we situate ourselves around it. Roger Eno’s technique is a very spare processing of piano melodies. The warbling effects periodically echo moments in his previous albums. These glimpses are refreshing and they reaffirm the comforting sense that we don’t know where we are headed.

More from this issue