“Everybody hate black people but want their style.”

–Iaintbias, VLAD TV

“X shot”

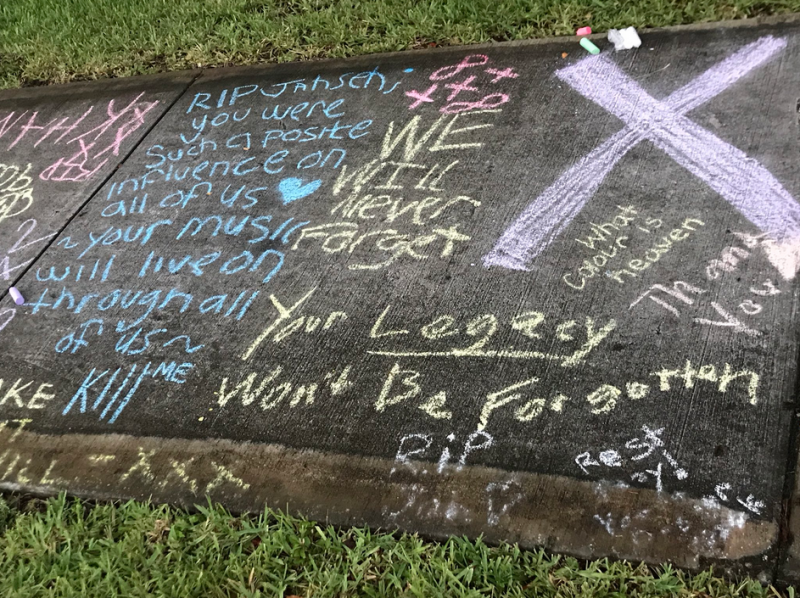

Here is a video, recorded live by a passerby for their Snapchat or their IG story. “X shot” is the caption. The words float over the footage of a boy with half a head of blue braids slumped in the driver’s seat of his car. Both butterfly doors of the black BMW are open. The boy’s left arm rests on his thigh. His head is tilted back, lips parted. Jahseh Dwayne Onfroy is his name, though fans know him as X (or XXX, XXXTentacion). He was shot and killed last month. He was 20 years old.

When I saw the footage online his death wasn’t confirmed. A bystander felt around for a pulse.

When I saw the footage online, I thought of Henry Taylor’s painting, brown body lifeless in the driver’s seat.

When I saw the footage online I felt sick. I thought first of his mother and what would she make of his hands, balled up like that.

Now unlike Taylor’s painting, there is no white arm of the law leaning into the car. In fact, no cops came until after, when his body was being removed from the car; when the car was being towed down the street. The motivation for Jahseh Onfroy’s death remains unclear. He had been shopping for a motorcycle near his home in Deerfield Beach, South Florida when his murderers ran up on him as he sat in his car. They made off with his Louis Vuitton bag.[1]

“Armed robbery” I read in the news, a framing in which theft of property eclipsed theft of life. Like the rap scene he dominated, the narrative of this killing is messy, distorted by historic cliché and expectations for blackness derived from images of 1990s “gangsta” rap. “Armed robbery.” “Random robbery.” Black bodies in drive-bys. Rising rap star. “Police looking for two black males wearing hoodies.” Suspects who fled in a black SUV. Jam Master Jay; Tupac Shakur; Notorious B.I.G.; Proof; the tragic coincidence that emerging rapper Travon Smart, AKA Jimmy Wopo, was shot to death in his car just hours after Onfroy.

Headlines in the wake of Onfroy’s death were disturbing.

Kyle Swenson of the Washington Post ran with this: “The nasty, brutish and short life of the chart-topping rapper killed Monday.” Swenson culled this crudely adapted quote from 17th-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651), an instructional text on the “nature of man” and society.

“He led with his fists,” Swenson says in his writeup. “Violence radiated off him.”

Swenson’s position is clear: the [black] boy got what was coming to him. There were many articles like this, plus a scrolling feed of indictments in the Post’s comment feed—the literary residue of a mainstream media faced with its own irrelevancy in a shifting pop-cultural landscape. The fact that XXXTentacion had name recognition at all struck some as abominable. Look how Chris Richards, also of the Washington Post, positions Onfroy’s hit single: “Good luck hearing it in the club, on the radio, out the cracked window of a passing Chevy Malibu, or anywhere else in three-dimensional space. But there it is at No. 65, enjoying its sixth week on the charts, breathing down the neck of Ed Sheeran’s ‘Galway Girl.’” The fact that Richards’ fear wafts through his stereotypical framing: the bad wolf is indeed at the door, poised to strike and take down the rosy white innocence of radio’s beloved balladeer. ABC News tried a different tactic of disempowerment: “Pronounced “Ex Ex Ex ten-ta-see-YAWN,” one pithy journalist explained. Never mind that “tentación” is Spanish, “desire” in a foreign tongue.

“Death is indiscriminate not just in its inevitability, but in its propensity for bleaching some of our darkest stains,” observed reporter Torii MacAdams in a remarkably facile feature on Onfroy’s murder for the Guardian. MacAdams’ choice of metaphoric analogy should raise some serious questions. While the public debate has centered on Onfroy’s morality and by association, that of his fans, less scrutiny has been extended to the overt demonstrations of racism activated by the mainstream media’s “par for the course” mentality when it comes to reporting the murder of a young, black male.

Question: to whom do we offer forgiveness?

The trouble with Onfroy is that he complicates expectations for blackness in contradictory and difficult ways. In certain respects, his biography conforms to a familiar script: Young black male, trouble. Young black male, violent. Young black male, incarcerated. Disowned by his teenaged mother, raised by his grandmother. Started life angry at women, relationships, the world. Sentenced with punitive measures. In and out of corrections facilities. Apprehended on charges of domestic abuse. Accused of sadistic acts—allegations not easily or willingly pardonable. Underpinning much of his early catalogue is a palpable, unhinged violence, a volatile collision of internal self-loathing (emo) and external flexing (hip hop) that characterized his sound and established a legion of teenage fans.

Onfroy’s very early work, songs and EPs produced and uploaded to SoundCloud when he was just 16 revel in fatalism. “So beware because the fall is all we know. An empty corpse around parading in the snow. Fuck. This is-th-this is all we know, this is all we know. This is it.”[2]

In the space of a year, his capacity for self-reflection expands: “There is no end to the pain. You must be numb. You are not alone,” he scrawls on a sheet of ruled, loose-leaf paper. He gets “numb” tattooed on his cheek. He writes notes to himself: “Talk to nannie everyday…Never be alone again… meditate everyday…target one thought…breath breath breath…liberation, from everything…” These writings, along with Polaroids of his naked brown body in a stark white room, become the album artwork for his first full-length debut, 17— a tone reminiscent of early 2000s emo-mixtape confessionals. Buried in the list of affirmations is a simple proposition that feels especially poignant: “Perform aggressive.” This statement brings to mind poet Claudia Rankine’s invocation of Jayson Musson’s directive on how to become a successful black artist, advising black practitioners to cultivate “an angry nigger exterior” because “black people’s anger is marketable.”

“To whom?” Is the follow-up question.

What other stories could support a boy born and raised in a southern town called Plantation? Think about this: black boy born and raised in a town called Plantation. Think about this, then ask him not to. Think about this but consider how he and his peers refuse to be bolstered to any one narrative. Onfroy, whose alleged criminal behavior cannot, can never, be justified, was in the process of reworking his self, staging alternative images for black male identity in a mainstream rap scene.

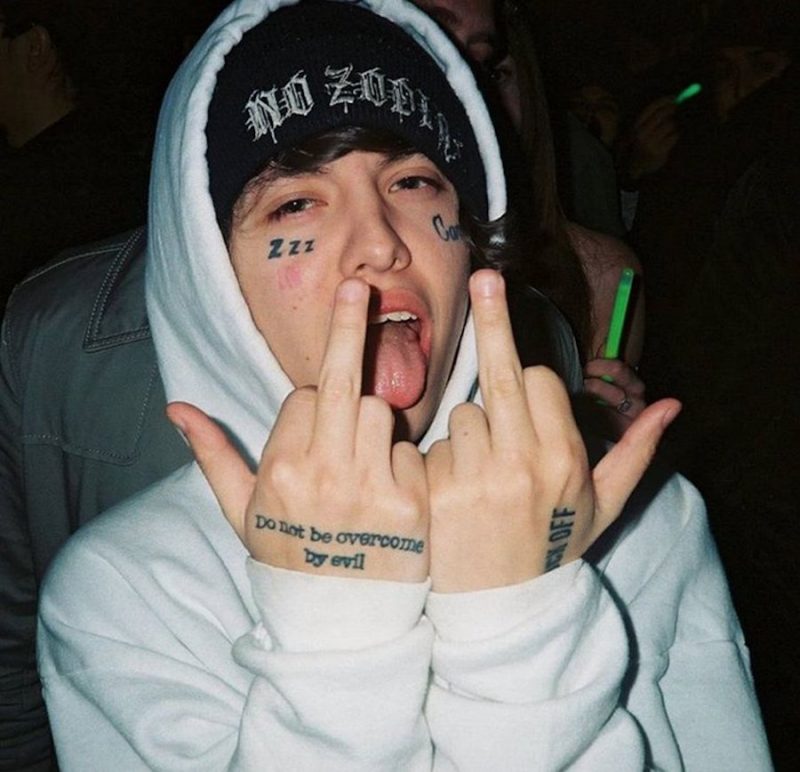

First he adapted the chain. No flashy medallion, no diamond-studded necklace hanging low on his chest. Onfroy preferred a goth style, chainmail bondage choker worn high and tight on his neck. An appendage that takes on significance when attached to the “nasty, brutish” black body (neck, wrists, ankles).

Then he rerouted the conversation.

“Ever seen a nigga hung with a gold chain?” Onfroy spits in the extended video version of his breakthrough track “Look at me!” Actually, the popular ratchet track is but a foil—Onfroy uses his most popular song as clickbait, exploiting it as 52-second intro that cuts abruptly to a virtually unknown song of his, “Riot.” It is this track that spans the remaining four and a half minutes of footage. As he raps, he’s suspended gallows-style from a tree, eyes bulging, hipster-grunge flannel shirt and branded band merch asking us to reconcile contemporary black aesthetics—increasingly indistinguishable from mainstream, multi-racial youth culture at large—with its violent, racially segregated past.

On screen, names and dates float above corresponding footage of beatings, lynchings, shootings: Emmett Till, Mississippi 1955; Philandro Castile, Minnesota 2016; Rodney King, Los Angeles 1991; Heather Hayer, Charlottesville 2017; Ferguson Riots, Missouri 2014… at times the audio recedes entirely. Onfroy enforces a rule of silence, affording the visuals full exposure.

When it aired last year this video caused outrage, its polarizing reception sparked by a closing scene which unfolds like this: two small boys, one black, one white, are led onto a darkened theatre stage. Onfroy carefully places a noose over the white boy’s neck and raises the rope. The boy’s feet twitch some. The black boy looks on.

Despite almost an entire video in which black bodies are assaulted, in which scenes from actual, well-documented murders of black men and women occupy its majority, in which Onfroy himself raps while noosed from a tree, headlines such as “XXXTentacion Hangs White Child in Controversial New Video”[3] or “Rapper Sparks Outrage After Hanging White Child in Music Video in the Name Of “Art”[4] or “Outrage as well-known rapper ‘lynches’ small white child in music video”[5] dominate its coverage. Conservative viewers perceived “reverse-racism”; these are the individuals presently praising Onfroy’s death in white supremacist forums. Just as tellingly, the liberal media’s response was one of uncomfortable silence, perhaps because the most astounding element of the video, more interesting than its sensational visuals, is that Onfroy’s message doesn’t entirely gel with the millennial grand-narrative of liberal identity politics. It’s a message that runs counter, say, to Childish Gambino’s “This is America,” despite both works’ reliance on black-death spectacle.

“If you don’t see the message, watch the video again,” declared Onfroy on social media when the piece aired. “If you think this is in support of Black Lives Matter, it’s actually not. It’s All Lives Matter.” As the latter half of the song transitions into an open letter to his African American community, Onfroy situates himself within black consciousness to speak to his peers from a position of sameness, othering the white world. “I know you got your problems, but brother, they got theirs,” he raps (“theirs” being white people). “This is not a game, quit violence and grow a pair.” W.E.B. Du Bois, in his revolutionary Souls of Black Folk (1903), proposed a “double-consciousness” of African American thought, wherein the white world is the strange outside through which black self-identity is supposedly mediated, formulating a “two-ness” of self identification[6]. Du Bois, writing at the turn of the 20th century, argues that for African Americans, “One ever feels his two-ness,—an American; a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.” A little over a century later, Onfroy, a Gen-Z born in 1998 into a globalized, post-internet, neoliberal reality, a grungey, gothy hip-hop head whose distinctive hair was parted in a metaphoric divide (one side bleached or dyed blue, the other “natural”) and who was photographed at the BET awards in a Janus type black and white mask, challenged the contemporary tribalist rhetoric of oppression. “But yo, you’d rather hear me say, “Fuck black prejudice!”, he yells towards the end of the track, promoting his belief that “victimization” stymies social progress because it nurtures resentment, that in fact it is inimical to harmonious civility. In an (arguably naive) manner shared by many in the racially-ethnically-sexually-diverse community of Gen-Z DIY music artists, Onfroy maintained that “Anybody can fuck with my shit. Black, white, Asian, Indian, muslim — I want anybody and everybody to be able to fuck with my shit. That’s the whole goal, to unite everyone.”[7]

This message, that the promise of America’s redemption narrative might be located outside of the groupings of identity politics, that it might ask us to consider difficult, unsavory truths across a spectrum unclassifiable, often ugly, experiences, and that we might consider the social-economic reality of the U.S. as the key perpetrator, is perhaps the most disruptive aspect of Onfroy and his peers in the SoundCloud emo-trap community.

It is abundantly clear that we are not living in a world rid of xenophobic thinking, in fact one might argue that such orientations to “other” are presently more visible and virulent than ever in the U.S. And yet large portions of youth culture refuse or deny the identity categories hitherto considered elemental in the theory and thinking-through of subculture. To move beyond identity categories in times of persistent racism is dangerous, not least because it challenges applications of language and makes it harder to interpret and analyze the very real, specific, and pernicious channels of power operating beneath the surface of representation. We cannot ignore the lineage and history of inequity in this country, but a growing contingency of youth are confronting previously held ideas about hierarchies of representation. In the SoundCloud rap community, it’s money that functions as the chief social arbiter.

When I started writing this essay, Onfroy was to be but a peripheral figure. What I wanted to talk about was how SoundCloud rap and the youth culture undergirding it exists within a new social reality. I had planned to write about SoundCloud rappers at large, about how this new generation of young artists are defining contemporary culture through consumerism, through wealth accumulation, through a radical demolishing of traditional identity vectors.

And then X got shot.

And then the headlines started in.

And then the stench of racialized bigotry descended.

And then my friend wrote a counter-narrative feature for Buzzfeed and received hundreds of hate-filled responses.

When I look at the SoundCloud community, when I look at Smokepurpp and Lil Yachty, Yung Lean; when I look at Lil Peep, Lil Tracy, Lil Xan, Lil Pump; or even when I look back further and beyond, look at Lil Uzi Vert, Young Thug or Post Malone, Tyler the Creator, Frank Ocean, and so on, the degree of racial, aesthetic and genre code-switching is mesmerizing. It’s exciting. But is it progress? Does it correlate to an accelerating racial wealth gap in the U.S.?[8] Should we draw a line between the hyper-consumerist attitude of the scene and their partiality to Xanax and Codeine —with the opioid epidemic at large? Generation-Z were born into a neoliberal regime and have come of age at its point of singularity. They have no choice but to tune in so they numb out. Mumble rap, a sub-genre of SoundCloud utilized to varying effect, is nothing if not a literal demonstration of sedated incoherence. Pain has the ability to destroy language, to destroy the capacity for speech and reduce it to sound; painkillers, the ultimate capitalist driver, insist on continuance, on maintaining, on carrying on. The slow, drawn out syllables or fierce, unbridled screams Onfroy employed in countless songs is a measure of conflict.

In many ways the confused, contentious space of SoundCloud rap parallels the disorienting instability of our present day politics. Last week Drake dropped Scorpion, his fifth studio album, on which there’s a song featuring Jay-Z. The closing lines, delivered with quiet contempt, are: “Y’all killed X and let Zimmerman live.” “Y’all” in this instance feels a propos.

[1] Dedrick Williams of Broward County has been arrested in conjunction with Onfroy’s murder.

[2] “The Fall” (2014)

[6] See Kevin Young’s thinking on this in his crucial The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness (Graywolf, 2012)

[7] XXL video interview

More from this issue