A live recording can thrust its listener into a moment in time. The raucous shouts of an interned crowd conjure up the night Johnny Cash spent at Folsom State Prison. The white noise in the mix of Donny Hathaway’s Live draws the ear to the texture of his voice, causing it to meditate on every word and breath. The crack of Lauryn Hill’s voice on her landmark Unplugged session only deepens its viscerality, highlighting its singularity.

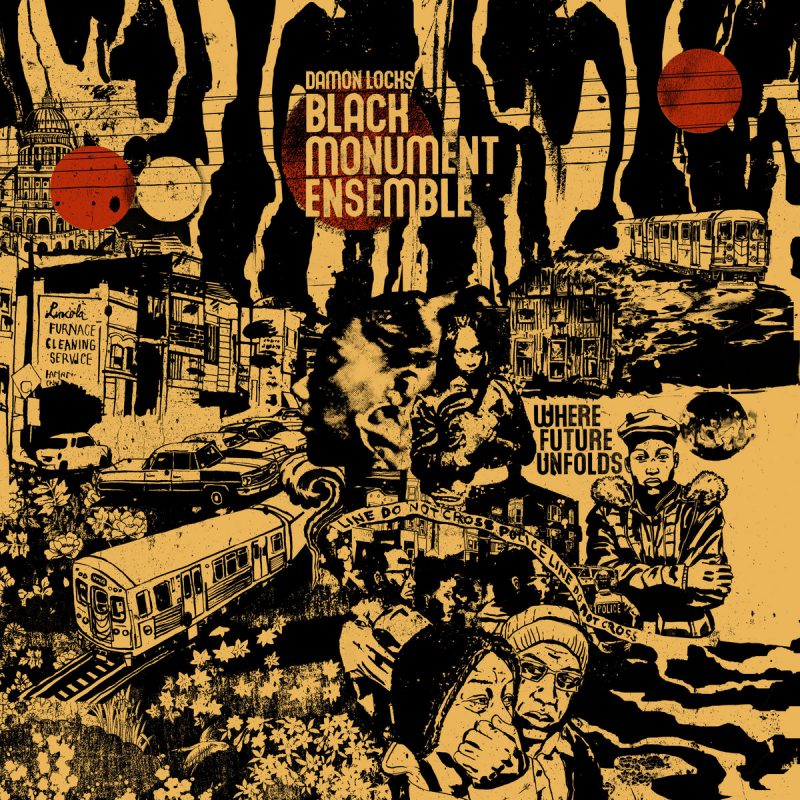

Where Future Unfolds, a recently released live album by Chicago experimental jazz group Damon Locks and the Black Monument Ensemble, does the same. At certain moments, it asks you to come with it to its place in time: Garfield Park in Chicago, November 15, 2018. As a young girl comes on to sing “Rebuild A Nation,” you can hear an older woman in the crowd encourage her: “Yes, baby!” As the choir chants during “The Colors That You Bring,” one member calls out to the crowd: “C’mon join us!”

But the album also transcends its moment, instead throwing you into multiple points in time. In one night, the band crafts a timeline, charting across Black histories to Black presents and Black futures. Late in the record, Locks plays a recording of a speech by an uncredited Black revolutionary who states: “The chief of police had decided that he was ready for a riot, and, so help him, there had to be one.”

Her declaration echoes through decades marked by police violence and Black uprising. The statement might be addressing the riots in Chicago in early ‘68, after Martin Luther King’s death, or the clashes with police later that year at the DNC. It could be referring to the Long Hot Summer of ‘67, when riots broke out across the Midwest. But, regardless of their origin, her words register kaleidoscopically. They cut to the feeling of Los Angeles in ‘92, after LAPD officers were acquitted for the beating of Rodney King. They call to mind protests that erupted in Chicago in 2014, after police murdered Laquan McDonald, firing 16 shots in his back.

And, of course, if listened to today, her words ring out in the spirit of this summer’s rebellion, culminating in mass demonstrations and riots. Her remarks perfectly encapsulate why the Minneapolis Police Department’s third precinct went up in flames this past May.

In 1903, Black historian and sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois stated that “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line.” Looking ahead at the dawn of the century, he foresaw its cycles of racial domination and insurgency. Du Bois would go on to devote several years of his life to studying Reconstruction — an archetypal example of this cycle of Black progress and white backlash. DuBois’s prediction implies that the problem of antiblackness is too vast to be undone by a single reform, or even a single movement. He knew that racial violence was the bedrock of the US and expected this terrorism to continue on long after his death. Reinterpreting Du Bois’s thought, Frank Kirkland has stated that “the problem of modernity is the problem of the color-line.” Kirkland suggests that Du Bois used “the twentieth century” almost as a placeholder, a term meant to signify the general future, including and stretching beyond the present day. Kirkland implies that the problem of the color-line is fated to traverse centuries, reappearing in different formations in each present moment. Both Kirkland and Du Bois encourage us to remain vigilant to the endurance of antiblackness throughout US history.

On Where Future Unfolds, Locks constantly reflects on this reiterative pattern of history. He uses the Ensemble’s one night in Garfield Park to shed light on the persistence of antiblack racism from past centuries into the present-day. The live record skips through time, speaking to the events and ideas of 1903, 1968, and 2020, all from purview of a single night in 2018. On “Sounds Like Now,” the Ensemble’s choir intones, “every morning there’s more talk of murder, every morning at least one less alive, I see all the same things happening…they tell the same line.” The choir reflects on the overwhelming circulation of Black death, brought on through the daily activities of systems of policing, incarceration and healthcare. They see a pattern not only in these killings, but in the remorseless statements of police departments, the tepid responses of politicians, and the clichéd platitudes of social media users. Though they employ different vocabularies, each of these groups tells the “same line,” expressing sorrow rather than taking responsibility, calling for piecemeal reform, rather than structural transformation.

As the choir continues, they further their analysis, repeating, “separate not equal, power to the government, never to the people…I thought in time things would change, in fact they stayed the same, how can people live with all this pain?” Over an entrancing guitar sample, they sound out Du Bois’s theory of history, connecting current systems of policing, incarceration and education to those of past eras. By repeating “separate not equal,” they evoke a history and present of thinly-veiled racial segregation. From the silent resegregation of school districts across the country, to the unchecked preservation of redlining, “separate not equal” still guides racial policy today. By calling out this history, the Ensemble collapses the century standing between their words and Du Bois’s. Their lyrics suggest that the Jim Crow architects of Dubois’ era, segregationist politicians of the mid-century, and white suburban parents of the new millennium are all cut from the same cloth — each living in the fiction of “separate but equal” conditions.

Their words cut through the sensationalism of recent news headlines, which imply that structural antiblackness is a novel epidemic that emerged alongside the pandemic. In this manner, their piercing insights echo not only Du Bois, but also Jewish Marxist philosopher Walter Benjamin. In one of his most well-known essays, Benjamin proclaims that “the tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘state of emergency’ in which we live is not the exception but the rule.” From Benjamin’s point of view, the oppressed are always living in exigent circumstances. He directs attention away from dramatized disasters to the routine emergencies of low-income life: food insecurity, eviction, probation, to name just a few. The Black Monument Ensemble’s conception of history matches Benjamin’s, born out of a knowledge that the circumstances of Black life have always been precarious. Benjamin warns one not to accept state narratives about a newfound emergency or a heroic leap forward in progress. Instead, one should meticulously study histories of oppression, and recognize how issues of today connect to the structural problems of past centuries. In Benjamin’s model, revolutionary movements must first recognize the endurance of oppressive conditions, before attempting to enact change. Throughout Where Future Unfolds, Locks and the Ensemble fulfill Benjamin’s call. Each of their songs reflects on the persistence of unlivable conditions, drawing on the wisdom of past movements to inform their current political outlook.

As the album continues, the Ensemble balances their awareness of these unchanged circumstances with an urgent demand for rupture with this chronology. Their lyrics, their samples, and their instrumentation vocalize the tensions between these two strains of philosophy: on one side lies recognizing an unchanged history, on the other side, envisioning the possibility of a different world. On “Solar Power,” Locks gives voice to this latter feeling. Guided by a powerful jazz clarinet solo, the Ensemble issues an anguished call for transformation. The choir sings, “love don’t turn from me, dig me from this hole, take me to a land where future unfolds, where we can feel sun, where we can feel free.” Arriving after the grave historical analysis of “Sounds Like Now,” their words feel pressing, rather than romantic. Locks suggests that envisioning the future is a conscious act, requiring an unflinching eye and a strong will. The group’s vision finds no common ground with the promises of the American Dream or the perfection of democracy. They reach out for a different future, defined by solace and freedom — a future that must exist for the flourishing of Black people.

Through a sample of another uncredited Black revolutionary, Locks again draws a parallel through eras of resistance, implying that principles of community-building forwarded by Black Power movement in the ‘60s and ‘70s must be repurposed to meet the onslaughts of violence Black people face today. In conversation about organizing strategies, the activist states:

We go about it the way that you go about daily work. First of all, you decide what you want, you establish your values and you start to live it. . . . You get yourself together first, and then you get your community together, and you get your neighborhood together.

Her words demonstrate that liberation cannot be endowed from an outside party, or won through a ballot box. It starts with determining one’s own desires for the world, and bringing those wishes into conversation with one’s community. In the years directly before and after this performance, there’s been an unprecedented number of people taking up this call through programs for mutual aid. Just as Locks points attention to past injustices to understand issues today, he gestures towards historic organizing strategies which have been put to effective use today. On “Solar Power,” the Ensemble suggests that a few individuals can start creating that place “where we can feel free.”

The revolutionary and the Ensemble envision a future unfolding through the small acts and aspirations of organizers and their communities. They suggest that new worlds are built out of collective necessity, with nothing but a few alike minds and a steadfast resolution. This model of world-making echoes that of Black feminist theorists such as Christina Sharpe, Tina Campt, and Saidiya Hartman, who each centralize the task of living and envisioning ‘otherwise.’ In her latest book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, Hartman chronicles the lives of young Black women at the turn-of-the-century, who exemplify the process of envisioning otherwise. Hartman describes envisioning otherwise as a necessary practice for young Black women living precariously in the cities of the mid-Atlantic. She writes:

No one else imagines anything better. So it is left to them to envision things otherwise; as exhausted as they are, they don’t relent, they try to make a way out of no way, to not be defeated by defeat. Who else would dare believe another world was possible, spend the good days readying for it, and the bad days shedding tears that it has not yet arrived?

Hartman sees an ascendant, revolutionary spirit in the daily lives of these women. Through their trips up from the South and their nights-about-town, they envisioned a world that centered their own pleasure, even as they faced severe criminalization, harassment, and poverty. Hartman finds no false optimism in their freedom dreams. She suggests that these visions were essential to their survival and resilience, providing a source of aspiration and nourishment when nothing else could. Envisioning a new world kept these women alive and ebullient, giving them the tools needed to think beyond histories and presents that promised only violence.

On “Solar Power,” the Ensemble engages in this practice of envisioning otherwise, daring to believe another world is possible, despite so much evidence to the contrary. Through the sampled speech of the revolutionary, which suggests that freedom starts when “you decide what you want, you establish your values and you start to live it,” Locks and the Ensemble reveal their kinship with these women. Both suggest that, to create a new world, one must spend their time “readying for it,” living daily life with this future in mind. Like the women, the Ensemble desires something better than this world, not out of some undue optimism, but out of practical necessity. In this context, the choir’s repeated lyrics, “dig me from this hole, take me to a land where future unfolds,” registers as a hymnal or mantra. The lyrics feel like a warm recitation, that keeps one away from despair, oriented towards the coming world.

As the record elapses, Locks and the Ensemble balance their acknowledgement of history with their envisionment of the future. On “Rebuild A Nation,” a small girl sings of the possibilities latent in state decolonization, swearing that there is still time to transform our nation “before we fall.” On “Power,” a sampled activist states, “we’ve been knocking on that door for 200 years but we haven’t been speaking his language.” His words remind listeners of the long history of antiblack violence, which has remained the structural fabric of the country despite centuries of Black resistance.

Ultimately, Locks suggests that the fusion of these two truths is “where future unfolds.” He implies that one must study the failures of past movements and the persistence of antiblackness to be able to forge a genuine abolitionist future. Over and over again, the album stresses the importance of knowing history in order to begin to break with it.

Its last song goes just a step further, reminding its audience of their own role in this history of repression and resistance. Over crashing drums and wavering clarinet, the choir wails, “there is power, there’s emotion, from a spark to where you are.” Their voices hold the weight of the collective history weaved through each of the previous songs. The crashing drums, screeching clarinet and wailing voices collide to create a tidal wave of sound, expressing anguish and ardor. They repeat these lyrics until it’s impossible not to connect them to the present moment — to see the line from the sparks of past revolutions to the uprising in the streets today: “There is power, there’s emotion, from a spark to where you are.”

After depicting the battle between forces of oppression and demands for a new world, the album thrusts you into this conflict. Like live albums before it, Where Future Unfolds reminds you of its moment of creation — evoking that one night in Garfield Park in 2018. But unlike most other live records, Where Future Unfolds doesn’t just thrust you into its moment in time — it calls you into your own. The Ensemble shows that each listener has their own role in this history, emerging “from a spark to where you are.” Whenever you hear the album, be that 2018, 2020, or decades into the future, the struggle it speaks to will be active, ongoing. One could find this truth depressing or fatalistic. But the Ensemble pushes you to envision otherwise: it asks you to visualize the future you want, and start to live it.

More from this issue