In a package of minutes there is this We.

How beautiful.

—Gwendolyn Brooks, “Riot”

[Socrates comes out of the house in a cloud of smoke. He is coughing badly.]

Socrates: What are you doing up on the roof?

Strepsiades: I walk on air and contemplate the sun

—from Aristophanes, The Clouds, lines 1913-15

Am I really implying that clouds talk to us?

—John Durham Peters, Marvelous Clouds

What Feels Immense, Encompasses

It wasn’t until fairly recently that I ever stopped to consider the logic of the clouds that I’ve so regularly passed under. By no means a climate scientist, I’ve never known exactly what causes clouds to drop rain. A friend recently reminded me that the big, puffy ones are called cumulonimbus, but I always forget the other scientific names and classifications. Rather than take on direct metaphors to their scientific properties, this essay will instead variously address clouds as a pattern, horizon, sound-form, abstraction, omen, vision, figment, fantasy, feeling, memory, ideology, barrier.

Sometimes, when I walk unannounced into a room or into a conversation, I find that there is already a pallor or a brightness there, a feeling that is cloud-like, or rather a cloud that is composed of the group’s feelings. These social formations exist outside and inside me and my fellows. These formations can motivate actions and bodies and are composed of both. This essay, nonetheless, will posit that a cloud is not merely defined by its immateriality or ineffability. Protesting or rioting bodies also move in clouds and their physicality and the materiality of their demands should certainly be taken quite seriously.

The logic of clouds is contingently iterative. In tracing out and hearing so many affective, material, and paradoxical clouds, I hope to have recorded something that can instigate the formation of future clouds. For the sake of preserving their motion, I hesitate to ever fully analyze their internal hierarchies. As clouds and types of clouds proliferate in this essay, I pay particular attention to those moments when the distinction between a cloud and its observer starts to evaporate. One of my questions here is what it feels like not to be within a cloud, but to actually take part in its processes.

The following prose vignettes — in transit along with their discussions of early spectral music, the philosophy of science, Old Attic comedy, late-capitalist media economies, and many different sorts of clouds — will most likely begin to interact in their own mutable and watery combinations. The many kinds of clouds that interest me are as real as the emotional and physical relations that they are composed of.

++++

It feels appropriate to begin by discussing what has clouded my own thinking recently, what has stuck my head so high in the clouds. I started to actively think about clouds when I received a call for papers on the topic in my email inbox by way of the English Department at New York University, where I am pursuing a master’s degree. As I began to reflect on clouds, I felt tempted to publish my thoughts within the seasonal production cycle and the semi-academic register of Soap Ear, this journal that I co-edit, rather than in an academic paper. I did want to test myself and my ideas, but I ultimately decided not to submit an abstract to the conference on clouds, partly out of fear of rejection and peer-review, and partly out of pride[1].

I sat in the succession of deferred moments leading up to that decision, in the guilty relief of abandoning a project I’d barely begun and the related cloud of ambivalence, without expecting any redemption for my choice. At first, I wanted to just forget about clouds for a bit, to leave the subject to some other critics and to move on to new skies. However, the form of the cloud stayed with me. The inkling of an idea I first had when reading the conference poster accumulated into a scatter-shot viewpoint, not so much a theory as a hazy lens that continued to grow hazier. Two courses I’ve taken at NYU with poet and theorist Fred Moten gradually sent me in directions I hadn’t expected to head.

After wandering in the dark for what felt like a long time, I suddenly felt myself deep in the midst of something pointed and aimless, something I couldn’t quite define and that I would certainly not reduce to some kind of intellectual “work.” Unlike the university or the “art-world,” I had perhaps always lived inside of this shifting social formation of cloud-watchers and movers and had just never seen it as such. Perhaps I had never been alone in here, either, and perhaps this cloud-of-sorts would somehow continue to help me intuitively grasp a radically inclusive ethics of collaboration. It was hard to know for certain because the feeling was only with me some of the time. I nonetheless resumed my study of clouds promptly and with renewed focus. I began to feel the porous potential of my object of study and the countless lines of flight onto which it led me.

++++

This personal example points to a new line of questioning. While recognizing that culture is not actually made up of water particles and is not, properly speaking, either one or several clouds, I am compelled to linger on a question of form in the broadest socio-political sense: what shape can we, my friends, comrades, family, NYU classmates, myself, and you, my readers, posit in the place of the rigid, classificatory, and oppressive visions of culture that we are taught so early on and are so often caught in thereafter? How do such alternative structures, or alternatives to structures, sound and feel? What might they say to us if they wanted to? What hints or examples of such patterns are already floating around us now?

As kids, my friends and I would find clouds in the sky shaped as perfect fluffy cars, wolves, and dragons. We would watch the sky avidly, and even try to push rogue clouds into place with the psychic forces of our mind’s-eyes[2]. This malleability and amorphousness might hint at the example of raw openness that the clouds in the sky offer as we model flexible and nurturing social organizations. Even as we work through the formal similarities between our communities and a particular understanding of clouds, that understanding is subject to changes, revisions, and new definitions. It can expand or contract, accelerate, descend, or disappear, all while its particles are still conserved within the atmosphere. There is a horizon of harmony in such a heterogeneous model and there is room for provisos, negotiation, and chaos. With these qualities in mind, one can begin to critically evaluate the utility in other writers and artists’ ideas of clouds as a model, futurity and limit.

I would also like to acknowledge that I came to the following predominantly western and Eurocentric lineage from the admittedly naïve belief that there are qualities, glimpses and perhaps even formal ideas to be salvaged from the ruins of the philosophical and cultural apparatuses that I’ve dragged myself through in academia. I am influenced by Fred Moten and his friend Stefano Harney’s writings about the university as institution in my hopes to have stolen some useful tidbits and stories for myself and you[3]. The meaning of clouds certainly did not begin in ancient Athens, and yet a woven path from Aristophanes, internet culture, and Karl Popper can still demonstrate something about the aesth-ethics of cloud-formations.

Towards a Genealogy of Clouds

My starting point in the following non-linear genealogy of clouds-as-imagination, clouds-as-sociality, should be taken as a cautionary tale for cloud-watchers and theorists. In Aristophanes’ 423 BCE Athenian play The Clouds, readers and audiences encounter a caricatured version of the philosopher Socrates, whose lifework amounts to the full-hearted evasion of truth via sophistry (the ancient art of specious argumentation), and whose gods, the Clouds, are at least as foolish, greedy, and self-inflated as the gadfly himself. In the ensuing encounters between a witless protagonist Strepsiades, his insolent son Phieidippides, and this cloud-obsessed Socrates, the play demonstrates the illogical and ridiculous pitfalls of worshipping physical and argumentative processes as if they were divine. If Strepsiades ultimately can’t reason his way out of his mountain of debts by learning Socratic argumentation in Socrates’ school (The Thinkery), neither can Socrates ever reason himself out of his foolishness and impiety.

What I find to be the most confounding part about this play is the logic (or cloud) of feeling that it coaxes the audience into. It is noteworthy that the comic-hero, Strepsiades, despite his base humor and laziness, does have a legitimate excuse for the mountain of debts that are burdening him: his son’s expensive habit of riding and stabling horses could have sent any Athenian looking for financial solutions. We may question Strepsiades’ motivations for enrolling himself in Socrates’ school and then sending his son there as a way to argue his way out of debt and yet in our world and his, this threat of debt is also quite relatable. When Pheidippides, fresh out of Socrates’ Thinkery, proceeds to rationalize beating his father with very arguments he learned from Socrates, we are surely intended to feel the weight of the insult. On finishing my re-read, I found myself caught both feeling Strepsiades’ motivations for finally burning down the Thinkery and questioning his mob mentality — grappling with this in-between.

Far from providing an airy, anti-hierarchical cultural vision, the ending to Aristophanes’ satire appears to fuel a cloud of rather reactionary political ferment. I want to think through Aristophanes’ message that a fixation on clouds, or an obsession with their ontology, can be at least as dangerous as any other prescriptive social structure. In tearing down these ambitious Socratic clouds, Aristophanes leaves us in a new kind of fog — a substrate that resembles the cloudiness of which my essay is also composed.

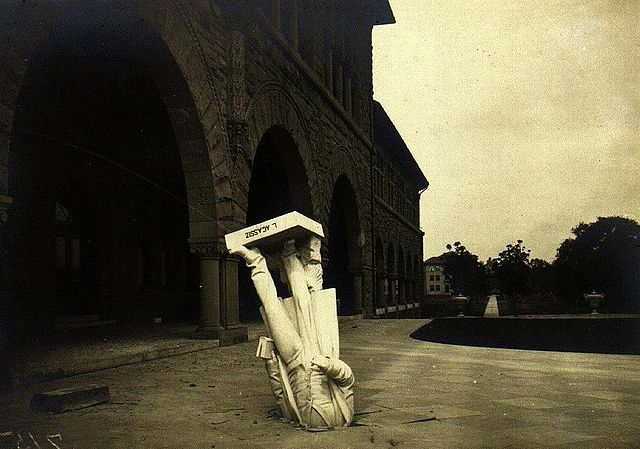

This cloudiness, the refraction of thought and justice, helps to explain why Strepsiades finally directs his anger and revenge not at his son or his debtors, but at Socrates and the Thinkery. It is important that Strepsiades, our everyman, does have a few moments of lucidity before finally mustering a mob of his slaves to exact revenge on the outlandish Socrates and his Thinkery (“My god, what lunacy. I was insane/ to cast aside the gods for Socrates” (ln 1887)). When Strepsiades orders his slave Xanthias to burn the Thinkery’s roof, he starts to exert a violent power that we half-expected of him all along. Despite the countless previous jokes at Strepsiades’ expense, his riotous mob now demands retribution for the growing injustice that at the center of which he and many fellow Athenians find themselves, the transgression of core Athenian values, religion, and social arrangements. In the course of these developments, the play implicitly brings up some ethical questions regarding the make-up of social clouds. Do we, as the audience, empathize, sympathize, criticize, join or resist this mob? And is this merely a question of interpretation or political definitions?

I have mentioned that clouds (and riots) are heterogeneous. They are tense. Strepsiades’ tiny mob is an uneven riot composed of several Greek slaves and him, the master, delivering orders. From texts like The Clouds, it is thought that most Athenian households in the 5th century BCE had around 3 or 4 slaves, and yet slavery wasn’t as pervasive as it was in Rome nor was it necessarily racialized in the modern sense. Some Athenian slaves could buy their freedom, some were sent to pretty grueling conditions in nearby silver mines. Attic comedy repeatedly put slaves at the brunt of jokes, but not enough is known about domestic slaves in 5th Century BCE Athens to determine the exact internal power-dynamics of Strepsiades’ mob. Some of this ambiguity is helpful for Aristophanes’ and our purposes; there is certainly an imbalance to be aware of, and yet it is difficult to locate.

Strepsiades and company’s aims obviously vary widely from the aims of the 1968 Chicago riots which broke out after the murder of Martin Luther King Jr., and which Gwendolyn Brooks so beautifully describes in her poem, “Riot.” Those Chicago riots were, closer to, but still distinct from the aims of the protests for Black life that have taken place this year, and those of the many aligned protests in the intervening years. During this year’s responses to police brutality and mass incarceration, I couldn’t help but join in a kind of frenzied solidarity. I shared in the widely experienced fear and fury of confronting the state’s muscle. On social media, on the streets of Brooklyn, and from the mouths of friends, I heard meanings, dreams, and contradictions moving rapidly and angrily in waves.

In talking as I have about The Clouds’ ending as a riot, I acknowledge that I am already blending the disparate roles of masters and slaves, actors and characters, performers and audiences, in unpredictable ways. I see this imprecision as a form of indeterminate solidarity and admit that I may be wrong. I am guided by the spirit of Brooks’ “Riot” to dive deeper into “this We”, to try to feel out what such a willful imprecision might mean, how it might sound.

++++

While researching this piece, the closest articulation that I could find of the elasticity and porous complexity of clouds I had in mind was in John Durham Peters’ book The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. Peters writes from a media theory standpoint that incorporates a natural world which can never simply be reduced to a scientific grasp. He encourages a “judicious synthesis… of media understood as both natural and cultural” in asking how actual clouds, seasons, soil, and even fire continue to signify in a world increasingly modified by humans. Peters even unearths many of the underlying power structures by which certain media continually shape our world.

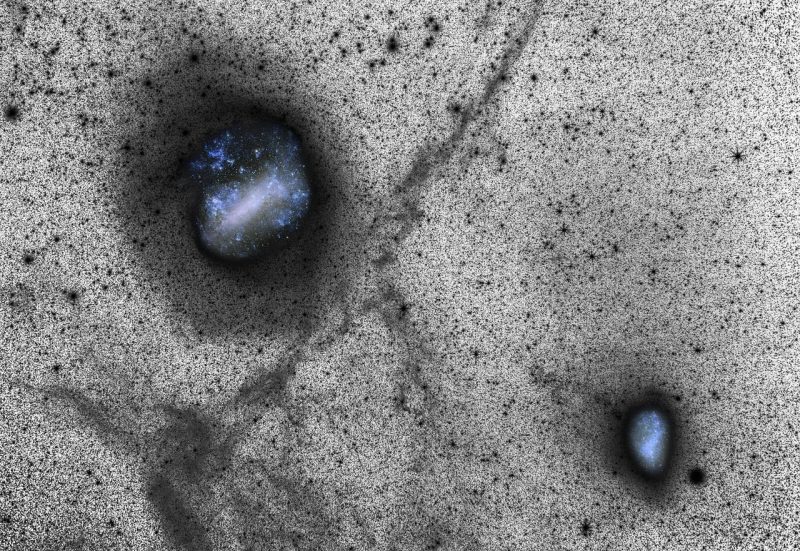

Peters’ writing has encouraged me to look out past my own metaphors of clouds as social formations (and cloudiness as the irresolute ambiguity of the relations in and between them), out to the skies beyond. If clouds are just floating masses of water droplets, then why can’t I stop thinking about them as shifting social formations? My obsession is surely related to an intuitive understanding of these cloud-bodies’ everyday non-linguistic signification as much as it is tied to my own intellectual and cultural background and the particularities of this project. Where Peters opened a field of inquiry, I saw an atmosphere in which to float and to propagate mobile formations and spaces.

I am taken by Peters’ historicizing explanation of the transition from the 20th century to the 21st, from Popper’s era to ours:

Unlike the mass media of the twentieth century, digital media traffic less in content, programs, and opinions than in organization, power, and calculation. Digital media serve more as logistical devices of tracking and orientation than in providing unifying stories to the society at large. Digital media revive ancient navigational functions: they point us in time and space, index our data, and keep us on the grid. (7)

The neoliberal surveillance of our digital existences cannot stop us from relying on this sense of orientation, nor can the dread of enmeshing oneself in this web of relations block how we might subtly benefit from this situating. So, while my choice to use either Spotify or Bandcamp to listen to a friend’s new record, for example, might change who profits immediately, what is shared across the platforms is the ready access — not just to sometimes-polished content, but also to a sense of dynamic, reaffirmed belonging in a broader formation. By listening on either platform, I immediately situate myself in a media economy or landscape; and with differing degrees of consent, I accept that the streaming platform will learn something about their audience’s preferences and habits while countless third-party companies will likely learn where the public is choosing to buy music these days.

Of course, Bandcamp and Spotify do supply markedly different micro-environments for orientation and listening. Where Spotify markets a lifestyle product of insatiable “discovery,” Bandcamp privileges a more finite consumption and ownership of music. At this stage in our techno-cloud-ocracy, most of us already feel the power-differential imbued into a streaming platform like Spotify — and Bandcamp for that matter. It is refreshing that in spite of his adherence to the seemingly eternal elements, Peters maintains that no media or structure is ever really permanent. Media form and define worlds and a firm reframing of clouds as media might define new orientations in our cultural landscape.

I am also inspired by how Peters confronts the messiness and slipperiness of his topic of “elemental media.” He acknowledges that some of his colleagues raised eyebrows at his central claim that media regularly function metaphorically as environments, and environments and elements as media. He accepts the awkwardness of approaching these natural systems as media and vice versa. If the term “media” becomes unruly when considered this broadly, what happens specifically to clouds when we understand them formally as a kind of geological conglomeration of human and non-human elements, of signs and signifiers? I find that some analytical control is lost and some clarity is gained.

++++

When he was composing The Clouds, Aristophanes appears to have understood the risk and precariousness of actually prescribing a model of social organization. One can observe how humor repeatedly patches over the absence of any new model of wisdom in the script that could stand in place of Socratic inquiry; the jokes nonetheless end up leaving audiences in an ethical vacuum for which the status quo or tradition seems to be the only solution. The closest that Aristophanes comes to offering a positive cultural model is in the context of a kind of allegorical debate between the Socratic Better Argument and Worse Argument. In this debate, we are apparently meant to align ourselves with Better Argument’s hyper-conservative and almost cartoonish celebration of a cultural order, enforced uniformly according to apparently arbitrary traditions (“first, there was a rule — children made no noise, no muttering” (line 1211)). The exaggerated, flowery language of these speeches would not have stopped a disgruntled Athenian aristocrat in the audience from nodding along with the core tenets of traditionalism. However, within the play’s dystopian satire, the Better Argument cannot withstand the power of the Worse and finally concedes: “O you fuckers, for gods’ sake take my cloak — / I’m defecting to your ranks” (line 1102-3). The perceived threat of the Socratic method to Athenian society is its insidious destruction of strongly held Athenian values; Socratic argumentative forms are taken as the medium of this threat.

As this play exposes absurdity and ill-will almost everywhere, we are left to feel the atmosphere (or cloud) of frustration building between the characters and audience; the tangible frustration can only be laughed away for so long, and it finally manifests onstage when the mob sets fire to the Thinkery roof and a smoke cloud envelops Socrates. Strepsiades’ powerful next line twists one of Socrates’ earlier lines about worshiping clouds into a pious homage to Apollo. In this entirely different context, Strepsiades parrots Socrates nearly word-for-word: “I walk on air and contemplate the sun.” It is crucial that at the play’s end, the general antagonism is not directed at the actual source of Strepsiades’ woe, his debt collectors, but instead at the caricatured intellectual, Socrates, and his dangerous method. When Strepsiades does confront his debtors earlier on, there is not nearly this same profound sense of justice-served that we feel in the burning of the Thinkery.

The force of this riot suggests a comparison or appraisal of Strepsiades’ (Aristophanes’) traditionalism against the parody of the Socratic method. I should note here that Aristophanes’ work is in fact one of only three textual sources portraying Socrates that were actually written during the philosopher’s lifetime (Socrates never wrote out his philosophies himself). With this knowledge it is difficult not to interpret the clouding over of discourse in The Clouds’ riotous ending as a kind of shadow-form of the philosopher’s real-life modes of argumentation. Rather than pitting the playwright against the philosopher one might instead conjecture about their common origins. And if the play shows Socrates caught in a hopeless loop of argumentation and impiety, one might wonder if Aristophanes is much better off. That is, in rejecting what he might call Socrates’ sophistry, Aristophanes still can’t avoid using the same ordinary language and logical structures that Socrates has always used to form his arguments.

If Strepsiades’ mob and the intellectual mob of Socrates’ Thinkery are shown to exclude one another, I am interested in asking how their contradictory movements also build a common mass, how they continue to permeate one another. How does the broader cloud of the discourse and bodies that make up the play and its performances morph into something else, including but not delimited by its contradictions, bodies, or ideas? How does that mass arrange itself?

Such broader formations of movements, and dogmas appear to be about as unwieldy as religious traditions. While discussing 5th Century Greek religious thinking, E.R. Dodds utilizes a phrase from scholar Gilbert Murray, “the inherited conglomerate,” to explain the utility of geology for describing the complex cloud of beliefs in the Greek Golden Era, when Aristophanes was writing:

The geological metaphor is apt, for religious growth is geological: its principle is, on the whole and with exceptions, agglomeration, not substitution. A new belief-pattern very seldom effaces completely the pattern that was there before: either the old lives on as an element in the new — sometimes an unconfessed and half-unconscious element — or else the two persist side by side, logically incompatible, but contemporaneously accepted by different individuals or even by the same individual… On questions like [that of “self” and “soul”], there was no “Greek view”, but only a muddle of conflicting answers.”(179-80)

Aristophanes’ play ultimately reveals the muddle, the puddle of contradicting coherencies and coherent contradictions that seem to accompany and constitute countless political and cultural visions.

And the wider cloud of cultural feeling in Aristophanes’ play does seem to have certain geological properties that might not be so familiar to a meteorologist or cloud-watcher. This cloud formation resembles the layers of the earth insofar as both constantly morph, grow, and dissipate. These massive clouds agglomerate new component parts or layers and always retain traces of old ones. Thus, in The Clouds, Aristophanic traditionalism (composed of disparate Greek values) gains as a new layer an interpretation of Socratic discourse (itself an agglomerate of different pre-Socratic and sophistic ideas). The broader earth/sky mass depends on and responds to Socratic principles, reforming in an instantaneous response to them. Here, some of the volatile nimbleness of the clouds is maintained in every clod of this cultural soil; each of these microcosms is both dense with tradition and mobile and unpredictable.

In re-reading the brutal comedy of The Clouds, I was surprised to discover traces of my own persistent and vivid fantasy of being encountered by others without any surfaces to one’s body, of “walking in air” inside a cloud in a sky full of surface-less clouds. As Socrates and Strepsiades both “contemplate the sun” in different ways, I in turn want to pursue the clouds they are peering through. Socrates’ false idols, the eponymous Clouds of the play, are just some of many decoys, veils, and lenses that enable my pursuit.

++++

This essay could have foregrounded any number of metaphors for the movements of culture, crowds, etc. in the place of clouds. I also heed Aristophanes’ warning that worshiping nature (clouds) or argumentation (method) can lead to a certain indolence or myopia. In selecting clouds, then, I hope I am not just relying on some common-sense notions of the skies or assuming an understanding of their basic scientific properties, both of which will vary wildly between individuals. Instead, I have found the countless variations and gaps between different perspectives and thoughts on clouds to serve as a niche for my own hazy words.

If John Durham Peters’ book suggests that the seepage between natural and social models I am exploring with clouds is nothing new, there is still much more to say about this cross-breeze within the long-standing speculative genres of philosophical discourse and cultural theory[4]. This metaphoric interchange can, for example, begin to explain how the philosopher of science Karl Popper’s ideas about openness in scientific methodology can bleed over into the fear of totalitarianism in his WWII-era book The Open Society and its Enemies (1945). The threat of totalitarian rule is at the core of Popper’s book of political philosophy, but I will spend more time here assessing another “nightmare” that appears in Popper’s 1973 lecture entitled “Of Clocks and Clouds.” While this next stop in my genealogy brings out further problems for my thinking in clouds, the lecture — delivered late in Popper’s career — also introduces enough useful vocabulary about the nature of clouds to merit a closer look.

Speaking at UC Berkeley, Popper set out to discuss human freedom of action, thought etc. as a product of interrelated physical systems and thus as explainable in strictly physical, as opposed to social or political terms. To categorize the various systems that make up the physical world, he posits an imaginary spectrum; if the systems that resemble clocks sit on the left side of the spectrum, as he puts it, those that resemble clouds are on the right. If clock-like systems are predictable, and even exact in their regularity, then clouds are best understood to be chaotic, unruly, and distinctly unpredictable. On this spectrum from clouds to clocks, Popper can chart any “system” we can name (as well as some we can’t), including the solar system, a playing child, and a family on a picnic. Of those three systems, the solar system is the most clock-like according to Popper, and the picnicking family is most unpredictable or cloud-like.

Notice how Popper’s clouds are put to work in this essay and embedded into a system of dynamic hierarchies. Popper’s spectrum allows him to posit a semi-determined model of our world in which unpredictable, quantumly organized systems (clouds) control and are controlled by other clouds. In the following thoughts, I want to examine a few blind spots in this lecture’s reconciliation of quantum theory and lived human experience in an attempt to challenge this privileged element of control which he places at the core of all “abstract” meanings.

I am particularly interested in evaluating what is so threatening about what Popper calls the “nightmare of the physical determinist” and how this threatening world-model compels a certain theoretical attitude. Popper attributes this nightmare of physical determinism to a Newtonian understanding of nature by which all of nature moves as an elaborate but predictable clock. The physical determinist — a label, he notes, that would describe almost every philosopher and scientist until the discovery of quantum theory — believes that all clouds are clocks if you look hard enough. Popper finds this physical determinist view not only oppressive but also ultimately incoherent and inaccurate. reduces the experience of freedom, human or otherwise, to a mere automatic response. It is a “nightmare” insofar as it contradicts logic and betrays our common notions and feelings of freedom. It turns the physicist and anyone else who believes the determinist theory into an “automaton” with no actual power over his own actions. All the same, one might ask if Popper’s approach doesn’t pose certain nightmarish conditions of its own.

Popper eventually brings to our attention that the nightmare of a Newtonian world is only one half of the broader threat to human freedom around which he is maneuvering; his more pressing critique in the lecture is directed at the complete indeterminacy posited by post-Newtonian quantum theorists and the philosophers that have championed their findings. Echoing scientist/philosopher Arthur Compton, Popper suggests that the “completeness” that some of these quantum theorists had claimed for their theories would indicate that quantum theory itself is yet another “physically closed system,” and in that sense unfree. By explaining all physical systems with complete chance instead of absolute determinism, these theorists have simply jumped out of the frying pan and into the fire. In a footnote (219), Popper warns that “purposes, ideas, hopes, and wishes could not in such a world have any influence on physical events; assuming that they exist, they would be completely redundant.” He here intends for us to find it unacceptable that our freedom, inclinations, plans, and the knowledge that we can freely act on these mental states, would all become “epiphenomal” to our actions in such a closed system. In fact, Popper doesn’t really give us another option.

Without generalizing about whether peoples’ sense of free will might actually be redundant to their actions, I will note how many and how thoroughly Black feminist writers have already thought through the lived condition of the persistent absence of freedom. From widely different approaches, Sylvia Wynter, Denise Ferreira da Silva, and Sora Han, for example, have each elaborated pathways by which this repeated, enforced, and deliberate denial of freedom through racial capitalism actually problematizes the notion of freedom altogether[5]. Each of these writers leads me to consider whether the sense of sovereign control over an individual’s own actions and thoughts is really so important considering that that sense of sovereignty always demands the subjection of something or someone else. Popper’s inability to fully envision the absence of freedom, to imagine it as anything other than a foggy “nightmare,” is an indication that his waking reality, real life, can only be defined according to a sovereignty or self-possession that he takes for granted.

When Popper tries to bracket off the social or political implications of his systematic worldview, the nightmarish social conditions of his theory emerge all the more vividly. In the course of the lecture he gives an evolutionary account of human cultural, technological, and scientific developments across history, which he describes as a kind of exoskeleton that humans have evolved or grown. In a very real, though partly metaphorical, sense, Popper thus attaches all current scientific and cultural inventions, theories, and methods to our bodies, whether or not we ever actually wanted these attachments.

We should be still more wary that Popper’s primary critique of Darwinism as a guide for social analysis (an umbrella that contains the most brutal of social-Darwinist theories) lies simply in its tautology and not in the power-imbalance it imposes. Accordingly, he writes that “we have, I am afraid, no other criterion of fitness than actual survival, so that we conclude from the fact that some organisms have survived that they were the fittest, or those best adapted to the conditions of life.” Popper’s refusal to positively define fitness, however, does not preclude his implicit privileging of a bio-political capacity of life (specifically humans) that keeps some alive under the control of others.

Are we simply supposed to accept chattel slavery as a past evolutionary stage or growth in human development? Whose development was it exactly? Certainly not all of humanity. And if, in evolutionary terms, slavery was eliminated by selection, then what is the purpose of its legacy, the lingering structures of racism and police violence for the US’ neoliberal “open society”?

I recall here E.R. Dodds’ geological metaphor for cultural shifts, in which belief systems are added or agglomerated while other components decay, and nothing ever dissolves. If, echoing Popper, one were to mount a comprehensive charting of human culture as cloud/soil, then the record of these forms of exploitation would most likely be infinitesimally inscribed in every particle of our cloud/soil along with every other layer of belief and their various shadow sides. We would need to compress these undesirable layers into smaller and more lucid discourses that can cut into one another like diamond into diamond.

++++

I still haven’t described exactly what it is like to be a part of a cloud, partly because there is no generalized answer to the question. The process of transubstantiation into a cloud-body is not facilitated by one particular feeling like lightness, weightlessness or any other mental state. A disciplined focus on one’s environment, though, does seem to be fundamental. But what does it really sound like inside of a cloud?

Hungarian composer György Ligeti was also interested in similar questions. In the 1960s and ‘70s, he moved into a transitional period of his work in which he was deeply concerned with a related problem of how to linger within a sound. At this point, after some exposure to early electronic music in the 50s and after a brief stint composing with Stockhausen at the WDR in Cologne, Ligeti began to integrate his assorted insights from working with tape and synthesis into his orchestral works. His compositional practice gradually homed in on dense polyphonic textures, a technique he called micropolyphony. In 1961 his piece “Apparitions” included extended sections of these sound surfaces, and then the following composition, “Atmospherès,” drew the technique out to one of its extremes. In “Atmospherès” at last, we find ourselves swimming through timbral rainstorms, clouds, and clear skies. These moments, static or shifting, are not landscapes or even soundscapes, they are themselves shifting, immersive atmospheres.

Ligeti also read Karl Popper. In 1974, the year after Popper published the aforementioned lecture, Ligeti wrote a piece of music for orchestra and a 12-piece women’s choir entitled “Clocks and Clouds.” He had this to say of the piece:

I liked Popper’s title and it awakened in me musical associations of a kind of form in which rhythmically and harmonically precise shapes gradually change into diffuse sound textures and vice-versa, whereby then, the musical happening consists primarily of processes of the dissolution of the clocks to clouds and the condensation and materialization of clouds to clocks (quote found in Steve Lacoste’s article for the LA Phil)

I am amazed that Ligeti intuitively avoids struggling with Popper’s fixation on freedom. He charts a musical process by which clocks become clouds and vice versa, showing that clouds seem to assemble, move, and ossify irrespective of our sense of control. Around the time of this piece, Ligeti’s focus shifted from timbral textures to rhythmic textures. His attention to timbre and overtones doesn’t erode with this new attention to time intervals so much as it takes on rhythmic dimensions.

The choir’s parts repeatedly emerge out of the orchestra’s cloudy textures to introduce either rhythmic, harmonic, or timbral textures, clock-like or cloudy. In one segment, the singers chatter monotone syllables that sound like a clicking clock (diga diga). And the clicking is also that of a slowing Wheel of Fortune, a chance procedure that still bears meaning to many, an indeterminacy that a few lucky gamblers might even beat.

But unlike John Cage, Morton Feldman, and Ornette Coleman, Ligeti was always a bit suspicious of the trend towards chance-based operations and improvisation that had swept the avant-garde at the time. In his written introduction to “Piano Concerto” (1985-8), about a decade after “Clocks and Clouds,” he concludes thus:

Musical illusions which I consider to be also so important are not a goal in itself for me, but a foundation for my aesthetical attitude. I prefer musical forms which have a more object-like than processual character. Music as “frozen” time, as an object in imaginary space evoked by music in our imagination, as a creation which really develops in time, but in imagination it exists simultaneously in all its moments. The spell of time, the enduring of its passing by, closing it in a moment of the present is my main intention as a composer.[6]

Ligeti’s time frames, his “spell[s] of time,” are structured by a resolution to be the composer and to set the objects in motion. He wants to bracket the process of his own composition but doesn’t worry too much about whether he has actually succeeded in doing so.

I like to think that Ligeti’s sense of humor and poetry in “Clocks and Clouds” and other pieces redeems his clinging to orchestration, determinism, and the objectifying of sound, as well as his pompous dismissal here of “fashionable postmodernism.” While some might see his humor as mystifying or obscuring the exertion of Popper-esque control over his musical objects, I see things a bit differently. The “’frozen’ time” within Ligeti’s musical objects can be explained by, but not reduced to, the magic of enclosing a duration within the present moment. And as my cloud-writings in turn attempt to honor the chaotic beauty of a riot across media and contexts[7], I find myself drawing inspiration from this dogged insistence on retaining some formality of orchestration.

++++

I can’t help but thinking that there are so many other forms of relation beyond what Popper calls a “plastic” — but firmly bi-directional — feedback loop, through which humans are controlled by and control their meanings, purposes, and aims. This “plastic control” allows for the freedom that Popper so desperately wants to establish, but we find that it is ultimately a freedom for humans to dominate and be dominated by meanings. This “plastic” system, for example, precludes us from forming ambiguous forms of interaction that aren’t defined by this principle of control and selection. A cloud is instead premised on multi-partied constellations of ambiguous relations and indeterminate hierarchies. When we take away self-possessed freedom as a goal for our atmosphere, all kinds of possibilities emerge.

To my ear, the distinction between control and interrelation lies in its cloudiness. Aristophanes has illustrated that the movements and makeup of clouds are not always innocent, but they are at the very least generative and subtle. There can be relationships and tension, contradictions and unresolved ironies either within a system or between systems. None of this needs to imply that systems or their component parts control one another. Why should it?

As I now recall fleeting memories of my childhood-self, daydreaming out the window of an airplane, I once again feel entranced and transported by that fantasy of somehow floating out there without leaving the shelter of the plane cabin. The feeling emerges not as a desire for guidance, friendship, or belonging, so much as the desire for a kind of motion, for slowness and for speed. Now, I also can’t help wanting to smell the petrichor again as soon as possible and for as long as possible. That wafting vapor of wet soil always melts me.

[1] Ever since applying for graduate programs in literary studies, I have cultivated a mix of fear, fascination, and suspicion of the academic conference circuit and its disorienting mix of academic hoop-jumping and productive communal discourse. Similar feelings of trepidation, I understand, are pretty common among new grad-students, in relation to a panoply of obligations and predicaments. I wonder, how does acknowledging these feelings here or elsewhere make explicit and thus more real this affective bond? More directly, how would I approach the isolation of my late-capitalist, media-saturated environs such that I could feel the distant slow suffering of those stuck in the same holes?

[2] Note that one can never actually bend the cloud with force or will-power. Only imagination and compromise does that trick.

[3]See The Undercommons by Moten and Harney

[4] For more on the particularly lethal colonialist and patriarchal manifestations of this metaphorical exchange between scientific theories and western philosophical ideas and for some possible ways out of these traps, see the work of Denise Ferreira Da Silva, as in “Difference without Separability,” Towards a Global Idea of Race and other pieces.

[5] See Han’s “Betty’s Case,” Wynter’s “No Humans Involved,” and Da Silva’s “Difference without Separability” for more on their critiques of Liberal ideologies of freedom.

[6] Ligeti’s essay about his work, “Piano Concerto”

[7] Many of my thoughts about riotous forms — on the streets, between friends, and in art-objects and thought-systems — were formed in a class with my professors Fred Moten and Lenora Hanson. The title of the class can perhaps stand in for a summary of our collective experiment in academic form: “Chatter, Mumble, Cant, Jargon, Stutter, Murmur, Rumor, Gossip, Curse, Babble, Vulgate, Pidgin, Petit Negre, Conspiracy, Common Wind: Abolition and the Hearing of Unheard Languages”

Works Cited

Aristophanes, et al. Clouds. Richer Resources Publications, 2008, http://johnstoi.web.viu.ca//aristophanes/clouds.htm

Ferreira Da Silva, Denise (2016). “On Difference Without Separability,” 32a São Paulo Art Biennial, “Incerteza viva” (Living Uncertainty). https://issuu.com/amilcarpacker/docs/denise_ferreira_da_silva

Han, Sora (2015). “Slavery as Contract: Betty’s Case and the Question of Freedom, Law & Literature,” 27:3, 395-416, DOI: 10.1080/1535685X.2015.1058621

Peters, John Durham. The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. Illustrated, University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Popper, Karl. Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach. Revised, Oxford University Press, 1972. http://www.the-rathouse.com/Of_Clouds_and_Clocks_Part_1.pdf

Wynter, Sylvia. No Humans Involved. Stanford, CA, Institute N.H.I., 1994. http://carmenkynard.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/No-Humans-Involved-An-Open-Letter-to-My-Colleagues-by-SYLVIA-WYNTER.pdf

More from this issue